If you ever visit the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) in London, you may notice a room in the Denys-Lasdun-designed building with an interesting name: the Censors’ Room. This room is not, as the name may imply, a place for the coordination of censorship, rather it recognises a post in the RCP with a long history. When Thomas Linacre founded the RCP in 1518, the founding charter specified that four physicians known as censors would assist the president with standards for medical education and practice. The censors became the examiners of the RCP, and until the 1830s, candidates were faced with a nerve-wracking oral question and answer examination in the Censors Room. Censors also protected the public and they could pursue physicians for malpractice and enforce discipline. Some well-known censors of the past include William Harvey (1578–1657), the physician who discovered the circulation of the blood, and Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), the founder of the British Museum.

Now, as part of the UK Medical Heritage Library (UK-MHL) project, the work of some 19th century censors is available online for the first time. One of those former censors was Lionel S. Beale (1828–1906). Beale had a long working relationship with the RCP as censor (1881–82), and also as curator of the museum (1876–88). His skill as a physician was recognised by the RCP with Beale becoming Baly Medallist (1871) and Lumleian lecturer (1875).

As a pioneer of microscopy Beale developed techniques for staining and fixing of cells and tissues, showing how microscopes could be used by physicians in their day-to-day work. The pyriform nerve ganglion cells are called “Beale’s Cells” in his honour. One of Beale’s best known works Disease germs: their nature and origin (1872) is now online. In the introduction, Beale detailed how he examined tissues to try and discover the causes of disease. He concluded that it was probable that disease originated in either people or domesticated animals. This was contrary to the work of others who argued that “external” agents were the cause of disease. This book is a must see for anyone interested in the early debates around germ theory and it includes beautifully drawn coloured plates.

“Disease germs: their nature and origin.”

Walter B. Cheadle (1835–1910) was another censor. He was an adventurer, who explored the Rocky Mountains in Canada with Lord Milton in 1862. They published a very successful book, The North-West Passage by Land (1865), about their journey. In the field of medicine Cheadle was best known for his work on childhood illnesses. In the RCP, Cheadle was a censor (1892–93), a senior censor (1898) and a Lumleian lecturer (1900). As an early supporter of women in the medical professions, Cheadle was one of the first lecturers at the London Medical School for Women.

Child nutrition and its impact on disease was one of Cheadle’s areas of interest. His book, On the principles and exact conditions to be observed in the artificial feeding of infants (1902) detailed much of his pioneering work and practice. He connected childhood illnesses with poor nutrition and outlined how a better diet could help children recover. There are sections on uses of milk and beef teas, the benefits of sterilisation and commentaries on scurvy and rickets. It gives a fascinating insight into 19th century diets and the deficiency-based illnesses to which that children were prone.

“On the principles and exact conditions to be observed in the artificial feeding of infants.”

Sir William Broadbent was a physician who spent many years working with the RCP as Croonian lecturer (1887), Lumlelian lecturer (1891) and as senior censor (1895). He ran for the office of president in 1899, but he was defeated. Broadbent was a distinguished physician and among his patients he treated two Princes of Wales as physician-ordinary, and Queen Victoria as physician-extraordinary. Broadbent was also an expert in neurology. One of his contributions to the field was ‘Broadbent’s hypothesis’, an attempt to account for the distribution of paralysis in muscles and the immunity of some muscles to hemiplegia.

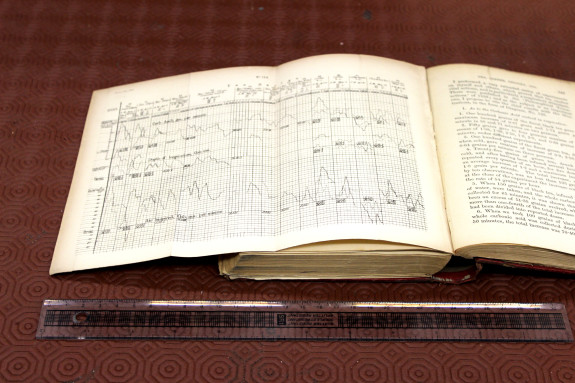

Cardiology was another area in which Broadbent excelled. Heart disease and aneurysm of the aorta, with special reference to prognosis and treatment (1906) was co-authored with his son John F.H. Broadbent. It grew from lectures delivered at the Harveian Society and the RCP. Broadbent reminisced about his early days as a physician – looking back to a time when there were no systematic ways of studying or treating heart disease. In this book Broadbent imparted his knowledge, and as cardiology developed new editions were issued with this cutting-edge information. The addition of colourful images illustrating what was being described makes this book a must read for those interested in the history of cardiology.

“Heart disease and aneurysm of the aorta, with special reference to prognosis and treatment.”

These are just three Censors who worked for the RCP in the 19th century, and many more will have their work included in the UK-MHL. The position of censor remains to this day and censors continue to work to improve medical education. However the RCP no longer holds examinations in the Censor’s Room; it is now used for ceremonial purposes.

Find out more about the RCP’s library, archive, and museum on our weekly blog, and follow @RCPmuseum on Twitter.

The following references were consulted along with the Munk’s Roll:

- M. Brockbank, ‘Cheadle, Walter Butler (1835–1910)’, rev. Anne Hardy, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/32386, accessed 19 May 2015]

- John Poynton (1935) Dr Cheadle and infantile scurvy, Archives of Diseases in Childhood, (1935), volume 10, no.58, 219-22.

Kevin Brown, ‘Broadbent, Sir William Henry, first baronet (1835–1907)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/32077, accessed 21 May 2015]

Michael Worboys, ‘Beale, Lionel Smith (1828–1906)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/30656, accessed 19 May 2015]

- D. Foster, ‘Lionel Smith Beale and the beginnings of clinical pathology’, Medical History, 2 (1958), 269–73.