We are delighted to be able to offer our readers this cross-posting from The New York Academy of Medicine blog series on Innovation in Digital Publishing.

The overwhelming tendency toward openness in digital networks presents both opportunities and challenges for contemporary scholarship, and in particular for the traditional structures that have facilitated and disseminated scholarship such as membership-based scholarly societies. Some of the challenges are obvious, and have been discussed in many other fora. The increasing demand for free access to products around which revenue models have long been built, for instance, challenges organizations to reinvent their fundamental orientation toward their stakeholders. For scholars, the network’s openness presents an increasing potential for information overload and an increasing difficulty in finding the right texts, the right connections, the right conversations at the right time.

All of these challenges are of course balanced by opportunities, however, as the network also presents the possibility of greatly improved access to scholarship and more fluid channels for ongoing communication and discovery amongst scholars. These opportunities suggest that an important role for scholarly societies will be in facilitating their members’ participation in these networks, helping to create new community-based platforms and systems through which their members can best carry out their work. Insofar as scholarship has always been a conversation—if one often conducted at a most glacial pace—the chief value for scholars should come in the ability to be full participants in that conversation: not simply getting access to the work that other scholars produce, but also having the ability to get their work into circulation, in the same networks as the work that inspired it, and the work that it will inspire. For this reason, the value of joining a scholarly society in the age of the network is less in getting access to content the society produces (the convention, the journal) than in the ability to participate.

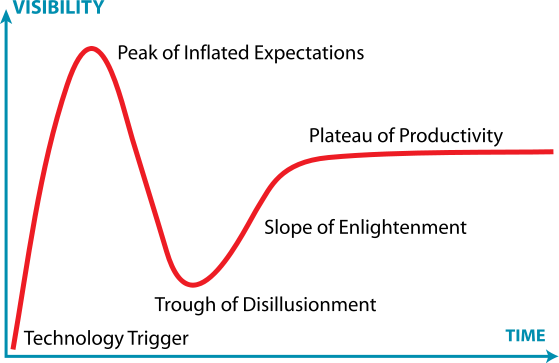

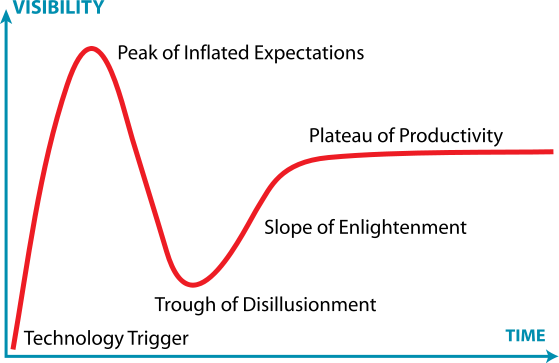

However, this opportunity points toward a deeper, underlying challenge, for societies and scholars alike: building and maintaining communities that inspire and sustain participation. This is nowhere near as easy as it may sound. And it’s not just a matter of the “if you build it, they won’t necessarily come” problem; problems can creep up even when they do come. Take Twitter, for instance, which developed a substantial and enthusiastic academic user base over a period of a few years. Recently, however, many scholars and writers who were once very active and engaged on Twitter have begun withdrawing. Perhaps the drop-off is part of an inevitable evaporative social cooling effect. Perhaps at some point, Twitter’s bigness crossed a threshold into too-big. Whatever the causes, there is an increasing discomfort among many with the feeling that conversations once being held on one’s front porch are suddenly taking place in the street and that discussions have given way to an unfortunate “reign of opinion,” an increasing sense of the personal costs involved in maintaining the level of “ambient intimacy”that Twitter requires and a growing feeling that “a life spent on Twitter is a death by a thousand emotional microtransactions.”

What is crucial to note is that in none of these cases is the problem predominantly one of network structure. If we have reached a “trough of disillusionment” in the Twitter hype cycle, it’s not the fault of the technology, but of the social systems and interactions that have developed around it. If we are going to take full advantage of the affordances that digital networks provide—facilitating forms of scholarly communication from those as seemingly simple as the tweet to those as complex as the journal article, the monograph, and their born-digital descendants—we must focus as much on the social challenges that these networks raise as we do on the technical or financial challenges. To say, however, that we need to focus on building community—or more accurately, building communities—is not to say that we need to develop and enforce the sort of norms of “civility” that have been used to discipline crucial forms of protest. Rather, we need to foster the kinds of communication and connection that will enable a richly conceived panoply of communities of practice, as they long have in print, to work in engaged, ongoing dissensus without reverting to silence.