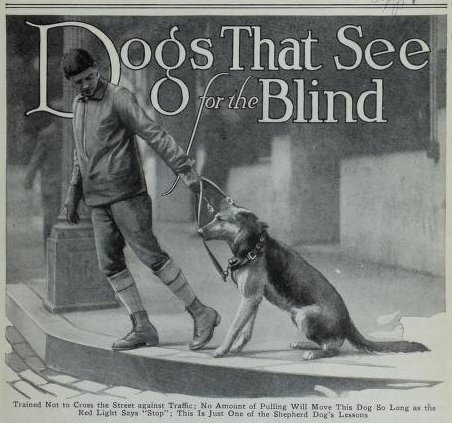

People with disability have been performing and working as musicians since time immemorial. In communities with no government welfare people had to work in order to survive, regardless of their level of impairment, and in areas where most of the available work was highly physical, music was often one of the few fields of employment available to disabled people.1 For example, in the southern United States in the early 20th century, genres like blues and country were influenced by large numbers of disabled performers, including Blind Lemon Jefferson, Joshua Barnes Howell and Hank Williams. Music was seen as an especially suitable career for blind people, and many cultures had musical traditions and instruments dominated by blind performers, including the hurdy gurdy in Europe and the biwa in Japan.2 In the Ukraine, blind minstrels known as Kobzars and had their own guild prior to the introduction of the Soviet Union in the 1930s.3 While blind musicians were usually well-respected, musicians with obvious physical disabilities often struggled to be accepted as serious musicians, instead plying their trade on the freak show or vaudeville circuits, as can be seen in biographies of Carl Unthan, Millie and Christine McCoy and Charles S Stratton in this collection.

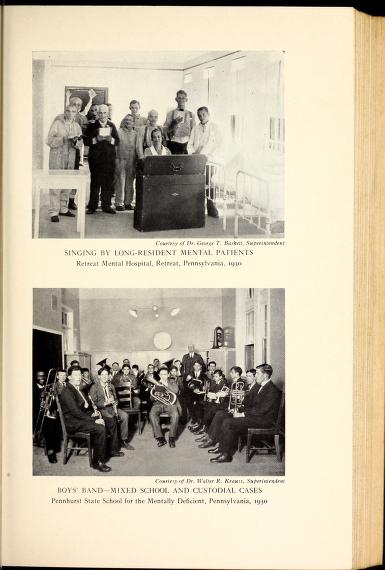

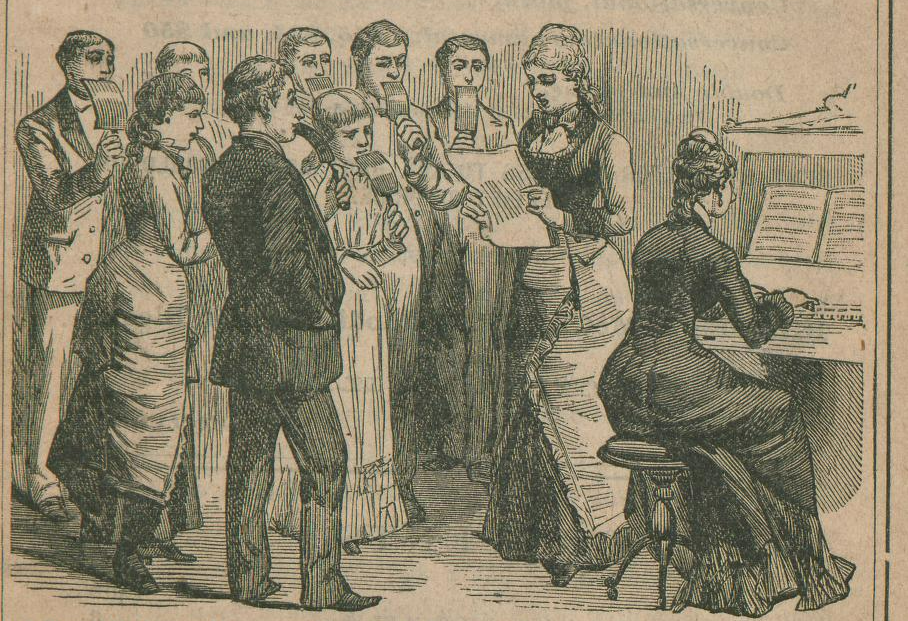

As well as providing employment for people with disability, music has also been used therapeutically in a variety of medical settings, from mobility training, to mood regulation and physical therapy. Many hospitals, asylums and residential special schools also featured their own choirs, bands and orchestras made up of staff and/or residents and these ensembles were often prominent in providing therapy as well as public outreach and fundraising for these organizations.

Regardless of whether they were performers, patients or both, people with disability have always been at the forefront of technological innovation in music, as they and their teachers and therapists create and adapt new instruments, technologies and techniques to suit their specific needs. In putting together this collection, I’ve taken a broad definition of music technology and education, including any information that shines a light on how musicians with disability created and negotiated their careers in an able-bodied world, alongside more technical information about instrument design, literacy and specific therapies. As such, the resource set is divided into five distinct sections:

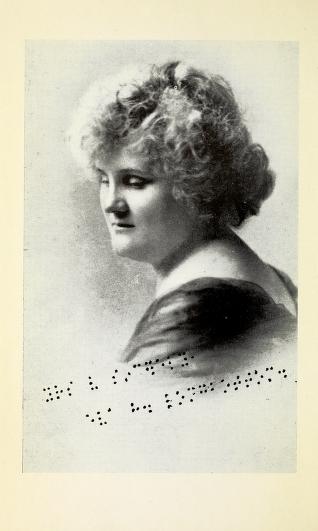

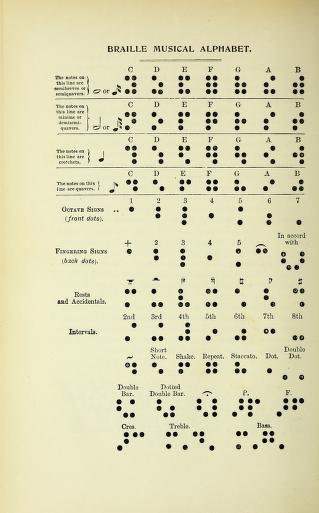

As we have seen, music is often seen as a logical and accessible career path for people who are blind or have low vision. The need for specialist literacy methods for the blind, in both language and music, also means that the blind community and their supporters have created a wide range of specific music resources and even whole libraries dedicated to clients with low vision. These factors mean that any collection on disability music will feature a preponderance of items relating to the blind community.4 This tendency is even greater in this collection, as the Medical Heritage Library includes substantial holdings from the American Printing House for the Blind and this data set is particularly rich in information about blind musicians and Braille and other music literacy methods for the blind.

Finally, this data set comes with a word of warning about the attitudes and language used within many of these documents. Language and attitudes towards people with disability have changed markedly, even within the current generation. Some of the language used in these documents, particularly towards people with intellectual disability or mental illness, is offensive by current standards. In most cases however, the authors are using terms, including ‘dumb’, ‘retarded’, ‘lunatic’ and ‘idiot’, which were medically accepted terminology at the time. More disturbing, in my eyes at least, are some of the procedures, attitudes and experiences discussed and displayed in these texts, some of which are dangerous and/or distressing, including the McCoy sisters’ tale of being kidnapped for display in a freak show, and the isolation of the members of the Culion Colony Leper Band.

Despite these hardships, what shines most brightly through this collection are the voices of the disabled musicians depicted within it. Among the biographies in Section One are a number of autobiographies, by Carl Unthan, Millie and Christine McCoy, Alfred Hollins and Eva Longbottom, in which we get the rare chance to hear disabled musicians discuss their own lives in their own words. We also see people with disability using music to build careers and livelihoods, from the manual designed to support blind music teachers in teaching sighted students, to representatives of The National Union for Professional and Industrial Blind travelling to Germany to assess new methods for educating blind musicians and piano tuners. This collection provides a rare glimpse into the history of disabled musicians, and the changing musical technologies and techniques they have used.

Biographies

Biographies

This collection includes the life stories of a range of musicians from the 19th and 20th centuries. They represent a wide range of disabilities including people who are blind, deafblind, congenital amputees, who have intellectual disability and/or autism, are short statured or conjoined twins. They also represent a wide range of performance traditions, from church organists to freak show performers to blues musicians.

It is a particular privilege to have access to the autobiographies listed below, as they give us a chance to hear in the musicians’ own words about the way they balance people’s expectations of disabled performers, with their own aspirations as artists. Armless violinist Carl Unthan longs to be taken seriously as a performer on the concert platform, but includes “tricks” like shooting a gun or writing a letter with his feet to please the audience. In contrast short-statured performer Charles S. Stratton, who worked under the stage name “General Tom Thumb” in P.T. Barnum’s travelling show, embraced his role in freakshows and managed to maintain financial control over his career, quickly out-earning his famous producer. For conjoined twins Millie and Christine McCoy, however, the decision about whether to perform in freak shows was not theirs to make. As African Americans living in the South in the mid-19th century, decisions about their lives were made by their slave owners, and at one point in their childhood, by their kidnappers. As we read the words of the McCoy sisters we must also be aware that everything they wrote had to be approved by their slave owners prior to being published.

Not every disabled musician has the privilege of being able to write even a censored version of their own story. “Blind Tom” Wiggins, for example, was another enslaved disabled musician. As an enslaved black blind man who was also autistic and/or intellectual disabled, he did not have access to literacy support or education. As a result, the biographies on Wiggins featured here had to be written by others.

Finally, it should be noted that not all of the biographies in this collection are directly about musicians, or even about people with disability. Helen Keller’s biography outlines how she used music to improve her speech as a deafblind woman, and Preacher in Song tells of the life of Josh White, a sighted man who did his musical apprenticeship working as a guide for blind musicians.

- Denham, Avery S. “Preacher in Song,” Collier’s 118, no. 20 (Nov. 16, 1946). Autobiography of Josh White who did is musical apprenticeship as a sighted guide for blind musicians.

- Harris, Sheldon. Blues Who’s Who: A Biographical Dictionary of Blues Singers. New Rochelle, New York: Arlington House Publishers, 1979. Features biographies of a number of performers with disability, including Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie McTell and Joshua Barnes “Peg Leg” Howell.

- History and Medical Description of the Two-Headed Girl: Sold by Her Agents for Her Special Benefit, at 25 Cents. Buffalo: Warren, Johnson & Co., 1869. Autobiography of conjoined twins Millie and Christine McCoy.

- Hollins, Alfred. A Blind Musician Looks Back: An Autobiography. Edinburgh and London: William Blackwood & Sons, 1936. The autobiography of blind organist Alfred Hollins.

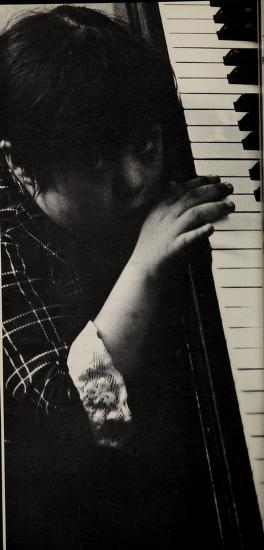

- Kling, Alice. “The Most Amazing Achievement in the History of Music Study: The Remarkable Story of a Student Who Has Been Blind and Deaf from Babyhood, yet Plays the Piano Fluently,” The Etude Magazine 46, no. 9, (September, 1928): 667-668. An interview with deafblind pianist Helen May Martin and her parents.

- Lady Campbell. “English, French and American Organists, Blind,” Outlook for the Blind 18, no. 1 (June 1924): 19-37. Focuses on biographies and training for blind organists.

- Longbottom, Eva H. Silver Bells of Memory: A Brief Account of My Life, Views and Interests. Bristol: Rankin Bros. Ltd., 1933. Autobiography of blind poet, singer and pianist Eva H. Longbottom.

- Macdonald, Colin. Notable Blind Musicians, Being the Story of Musicians Educated at the Royal Dundee Institution for the Blind. Dundee: Royal Dundee Institution for the Blind, 1920. Includes Henry Marshall, Joshua S Brand, Duncan McPherson and others.

- Mallinson, George and Jacqueline V. Mallison. “…And the Blind Man on the corner who sang the Beale St Blues,” Blindness: AAWB Annual (1972): 71-93. An article on the contribution of blind performers to the Blues.

- McCloud, Barry. Definitive Country: The Ultimate Encyclopedia of Country Music and Its Performers, First Edition. New York: Perigee, 1994. Features biographies of a number of disabled performers including Alfred Reed, Hank Williams and G.B. Grayson.

- Nicholson, Lois P. Helen Keller: Humanitarian. New York: Chelsea House Publishers, 1996. Biography of the famous deafblind author and activist.

- Sawyer, C. M. History of the Blind Vocalists. New York: J. W. Harrison, 1853. Includes biographies of Charles Rossiter Coe, Anna Smith, Mary Brush and others.

- Thumb, Tom. An Account of the Life … of Charles S. Stratton: The American in Miniature, Known as General Tom Thumb, 25 Years Old, 25 Inches High, and Weighing Only 15 Pounds. With Some Account of … Dwarfs. London: T. Brettell, 1845. A playbill featuring a (somewhat fictional) biography of Charles S. Stratton also known as General Tom Thumb.

- Unthan, Carl Herrmann. The Armless Fiddler, a Pediscript: Being the Life Story of a Vaudeville Man. London: G. Allen & Unwin ltd, 1935. The autobiography of armless violinist Carl Unthan.

- Wilson, James. Biography of the Blind: Or, Lives of Such as Have Distinguished Themselves as Poets, Philosophers, Artists, Etc. Birmingham: Printed by J.W. Showell, 1835. This collection features a number of blind musicians including Turlagh Carolan, Denis Hampson, William Talbot and a description of how Handel coped with blindness in old age.

Music in Institutions

Music in Institutions

Hospitals, asylums and other medical institutions have often historically included music as part of their services. Music can be used in many therapeutic contexts, including to improve physical dexterity, for relaxation, to improve mobility and communication and to provide leisure and career options. Prior to the invention of recorded music, the only way to provide this music was through live performance and as a result, many institutions featured their own bands, orchestras or choirs made up of staff and/or residents. These ensembles not only provided music within the institution but they also provided important outreach services by performing at special events like hospital open days, and for celebrations in their local communities. For community members, seeing disabled hospital and asylum patients gainfully employed in music making also served to integrate them into society, and in some cases even provided patients with future avenues of employment after discharge.

Within this resource set, the most detailed description of the varied uses of music in hospitals and institutions is Willem van der Wall’s 1935 Music in Institutions which claims to be the first book with the “systematic representations of aims, methods and cautions to be observed in this field of music in welfare work.” It covers a range of institutions, including residential schools and correctional institutions as well as hospitals and asylums. Of particular interest is Chapter X “Music for the Physically Infirm and Mentally Deficient,” outlining specific techniques and technologies for music therapy and education for people with disability. As can be seen by the title of the chapter, the language used is confronting for modern readers, as are many of the assumptions behind it. For example, teachers of the blind are told to support and encourage their pupils to seek careers as musicians, instrument makers or piano tuners, but the assumption is that “crippled” (physically disabled) and “mentally deficient” (intellectually disabled) pupils will be incapable of reaching such heights, stating “No mentally deficient person can be artistic in the technical sense of the term, because he lacks the intellectual discrimination essential for aesthetic understanding and artistic action.”

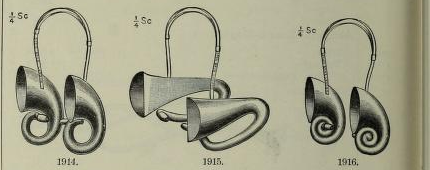

It is not just attitudes towards people with disability that have changed since this book was published in 1935, objects now considered commonplace, everyday items are discussed as the latest in adaptive technology. This is made evident in the section on convalescent wards which discusses the therapeutic benefits of employing newly available headphone technology. This meant that for the first-time patients could listen to the radio without disturbing those in the beds around them. As with all new technologies, they were far from perfect, and involved all listeners having their headphones attached by a cord to a radio at the front of the room. This meant that listeners could not choose their own volume or change channels, but it still allowed patients who did not wish to listen to remain undisturbed. The section on Music Room and Equipment also provides an interesting example of the kind of equipment used in music education and therapy at the time. Although there is little information on adaptive equipment specifically, it does outline the way sound proofing, music playback equipment and instruments were managed in the 1930s.

The Lantern was the regular newsletter of the Perkins Institution and Massachusetts School for the Blind. Founded in 1829 it was the first school for the blind in the United States and continues to operate today under the name Perkins School for the Blind.5 The Medical Heritage Library’s collection includes an anthology of issues of The Lantern published between 1935 and 1951. Braille editions of these issues were also produced. Although The Lantern is not about music specifically, but about the school’s activities more broadly, the many articles about music highlight the central part that music played in its curricula and in the lives of its students and teachers. There are many references to concerts and other musical activities and achievements by both current and former students and staff. Highlights include the March 1936 edition which contains the results on a survey on blind music education, the December 1938 issue with an obituary for the school’s long-time music teacher Edwin L Gardner and a description of a new service to create copies of braille music on demand (until that point, blind musicians had been limited to specialist braille collections). The same edition also reports on the installation of headphones in the deafblind department (just three years after their use was suggested in Music in Institutions above), allowing students with residual hearing to better take part in chapel services. The December 1940 edition outlines scholarships, including music scholarships, available to students, and describes the fact that some senior students are also employed by the school to teach music parttime to younger pupils, while the December 1943 edition gives an overview of the wide range of musical activities held at Perkins in the preceding year.

The final two entries in this section refer to a cultural and medical phenomenon which fortunately no longer exists, that of the leper band. Prior to the introduction of successful treatments for leprosy in the 1940s, people living with the illness were often segregated into ‘leper colonies’ in an attempt to avoid the illness spreading into surrounding communities. Segregation meant that such colonies were forced to provide their own entertainment and many formed their own bands. As with hospital and asylum bands, these ensembles could also be used for public outreach and fundraising – as long as they performed at a safe distance from able-bodied audiences. Indian poet Arun Kolatkar (1932-2004)6, who was well-known for writing about social outcasts, describes witnessing one such ensemble.

This collection includes descriptions of two 19th-century leper bands, one in Hawaiian, and the famous Culion Colony Leper Band from India. While these references describe the bands, they also give us an insight into the lives of the residents of these remote colonies, and the way they were seen by the few people brave enough to visit them.

- Bird, Isabella L. The Hawaiian Archipelago: Six Months among the Palm Groves, Coral Reefs, & Volcanoes of the Sandwich Islands. London: John Murray, 1890. Includes descriptions of a local leper band.

- The Lantern. A collection of newsletters from the Perkins School for the Blind between 1935 and 1951. Contains many references to musical activities by the schools current and former students and teachers.

- Van de Wall, Willem. Music in Institutions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1936. A detailed description of the way music was used therapeutically in hospitals, prisons, asylums and residential schools in the 1930s

- Woolley, Monroe. “Curing the Dean of Diseases,” in The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review 56, no. 1 (January 1916): 9-13 Includes a description of the famous Culion Colony Leper Band.

Accessibility

Accessibility

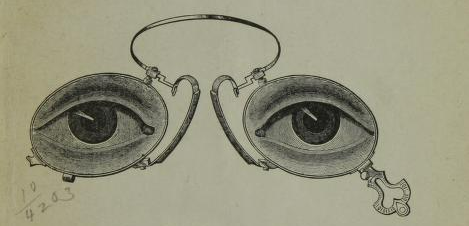

As has already been demonstrated, musicians with disabilities have always taken their place on the concert platform, but in order for them to do so, their access requirements need to be met. These requirements can include a wide range of adaptations, including making stages and venues physically accessible, appropriate sound and lighting systems, adaptive musical instruments and access to alternate forms of music literacy such as braille and various computer programs.

As with Music in Institutions (1936) described above, Arts and the Handicapped (1975) provides a snapshot in time, of the availability music technology and its accessibility. Concentrating on the American context, it outlines current best-practice standards for patron accessibility to artistic events and buildings, long before the introduction of the Americans with Disability Act (1990). It then provides profiles of major arts community and education programs around the country, with a focus on their accessibility. Although this book covers all artforms, a number of the profiles discuss music programs and technologies they use that are specifically designed to be accessible for people with a range of disabilities.

The report of the Technology-Related Assistance for Individuals with Disabilities Act of 1988 is notable for the testimony of Teddy Pendergrass, a singer who returned to his professional career after becoming quadriplegic. Pendergrass’ manager, John Hartman also attended the hearing. Pendergrass testified that, with the use of adaptive technology, he is “able to compete on an equal basis with any musician… When it comes to my music, my disability is not important,” however he also noted that technology was useless without training and support to learn how to use and maintain it. The report does not outline the exact nature of the devices that Pendergrass was using, but they do note that he was only making “simple modifications’ to allow him to use ‘sophisticated electronic musical technology.” Key to making these modifications work, according to Pendergrass, was the personal involvement of the disabled person in the design of the technology they would use.

Art for Humanity’s Sake (1976) tells the story of the development and exhibitions of the Mary Duke Biddle Gallery for the Blind. The Mary Duke Biddle Gallery was conceived as a place that would make fine arts accessible for people who are blind or have low vision. Although the main focus of the gallery is on tactile art, a number of aural sculptures and displays are mentioned. Blind visitors are shown playing traditional drums in one museum display, while the gallery also featured a range of listening rooms, headphones and loudspeaker devices to ensure communication with blind patrons throughout the premises. There is also a profile on a sound-sculpture created by Francois and Bernard Baschet which allowed patrons to interact with it to create their own music. Blind jazz pianist George Shearing is pictured playing the sculpture.

Hobbies of Blind Adults (1953) contains two sections relevant to this resource set. The section on music discusses the availability of braille music, as well as another tactile music notation method then being developed for popular music, as well as hints and tips for performers, like ways to navigate to correct seating positions in a choir, and printing braille music on black paper to match choir robes. The section on sound recording or the “camera for the blind” as it is referred to, outlines the various advantages and disadvantages of the three main methods available at the time: tape recording (reel to reel), wire recording and disc (record) recording.

New Outlook for the Blind (1973) contains all the issues of the journal aimed at professionals working with blind people released in that year. These issues contain a range of references to music for the blind, including in education, employment and leisure as well as in rehabilitation and mobility training. A highlight is a discussion of music education and the suitability of various musical instruments in the October edition, however, the journal’s paid advertisements and classified sections also provide a wealth of information on technologies available to blind people and those who worked with them in the early 1970s.

Education and Literacy

Education and Literacy

This section is the largest in this resource guide. It is also the most focused on musicians who are blind or have low vision, demonstrating the central place that music education has in educational and vocational support for that community, as well as the extra educational resources required to make music literacy accessible for people unable to read print music. Indeed, there is only one resource on this list that is not solely or predominantly devoted to music education for people who are blind or have low vision, and that is John Kitto’s book titled The Lost Senses (1845). The book contains two volumes, the first about deafness and the second about blindness. In volume one Kitto who was deaf himself, includes a chapter titled “Percussions” that outlines the methods that deaf people can utilize vibrations to understand the sounds around them. There is also a short section starting on page 196 about music appreciation for deaf listeners. Volume two contains a chapter on blind musicians.

A Music Library for the Blind and Physically Handicapped outlines the collections of the Library of Congress’s Music Section of the Division for the Blind and Physically Handicapped available in 1976. The collection was available by mail order and included scores, instruction manuals, and books about music in Braille and large print and on cassette, record and magnetic tape. The available scores demonstrate the expectations of suitable instruments for blind people, with an extensive piano and organ section, smaller collections for violin and voice and ‘considerably less’ for other instruments. The book also details learning methods for blind musicians, describing packs containing sheet music (for sighted accompanists), Braille and large print copies of solos and a cassette recording of the solo, broken into small segments for ease of learning. Although the library catered for both blind and physically handicapped patrons, there is no mention of technologies specifically for people who are physically handicapped, although some could, of course, have benefited from access to audio recordings of printed material. The New Braille Musician (1973 & 1975) and That All May Read: Library Service for Blind and Physically Handicapped People (1983) also describe music collections for the blind.

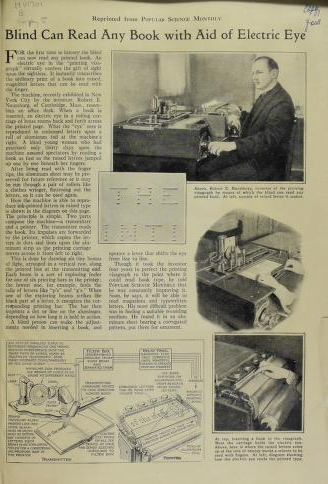

By comparing the various resources on music literacy for the blind in this collection, we can see how systems have changed over time. The earliest system described is in Apparatus to Enable the Blind to Learn and Teach Music (1815). This outlines a music notation system prior to the introduction of braille. Although the apparatus is unfortunately not pictured, the article describes music notation that is not punched into card, but made up of brass characters set up on a three-foot long wooden board. As cumbersome as this may sound, it is described as being far easier than a previously available system which was apparently made of 600 wooden pieces.

By 1880 the Ontario Institution for the Education of the Blind’s Annual Reports outline three currently available methods of music notation, all using embossed card, highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each. They were braille, embossed standard notation and the New York Point System. By 1935 Alexander Reuss’s book Development and Problems of Musical Notation for the Blind focuses predominantly on braille, while also giving a short history of the development of various types of notation. Reuss also emphasizes that many blind musicians have successful careers playing only by ear, and he also discusses ways that blind and sighted musicians can express their musical ideas to each other. By the 1970s, The New Braille Musician still features braille, including detailed descriptions of technical details like notating slurs (1975), and a description of a new system to use computers to print Braille music for the first time (1973).

This resource set also includes a number of articles on professional development resources for blind people working in different aspects of the music industry. History of the Education of the Blind (1910) highlight the suitability of both piano and organ as instruments for blind performers, particularly emphasizing the career stability offered by positions as church organist. It also includes a section on piano tuners. Report of Deputation of Musicians and Tuners to France and Germany (1930) outlines a research trip to Germany by British musicians and piano tuners to learn about the latest supports available for blind people working in both fields. The Blind Musician and His Training (1922) and Higher Education for the Blind: A Visit to the Royal Normal College and Academy of Music (1887) both discuss professional education for blind musicians while, in contrast, Teaching the Music Business (2004) and The Blind in Music Education of the Sighted (1951) both discuss methods blind teachers can utilize in supporting their students (sighted or otherwise).

- Burford, Leonard. “The Blind in Music Education of the Sighted.” PhD diss. Columbia University, 1952. A doctoral thesis written by blind music teacher Leonard Burford on techniques for teaching music to sighted pupils.

- Cooke, Matthew. “Apparatus to Enable the Blind to Learn and Teach Music,” 1815.

Describes an early 19th century machine for teaching music literacy to the blind. - “Higher Education for the Blind: A Visit to the Royal Normal College and Academy of Music,” (1887) A description of educational courses available for the blind available at the Royal Normal College and Academy of Music in 1887.

- Holbrook, M. Cay, Tessa McCarthy, and Cheryl Kamei-Hannan. Foundations of Education, Third Edition, Volume II: Instructional Strategies for Teaching Children and Youths with Visual Impairments. New York: AFB Press, 2017. Chapter 16 on arts curriculum is particularly relevant to this collection.

- Illingworth, W. H. History of the Education of the Blind. London: Sampson, Low, Marston and Company, Ltd., 1910. Discusses the suitability of careers in music, particularly as organists and pianists, for blind people.

- Kitto, John. The Lost Senses. London: Charles Knight & Co, 1845. Contains two volumes – Deafness and Blindness. Written by John Kitto who was deaf himself.

- Konagaya, T. “Education of the Blind in Japan,” Outlook for the Blind 45, no. 2 (February 1951): 33-38. Article focusing on music education for the blind in Japan.

- Levine, Audrey. “Teaching the Music Business,” The Blind Teacher 27, no. 1 (Spring 2003): [3-6].

Reflections from a blind music teacher. - Library of Congress. That All May Read: Library Service for Blind and Physically Handicapped People. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1983. Description of the Library of Congress’ National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped in 1983.

- Music for Blind and Physically Handicapped Individuals, Fall 1976. Describes the collection of Library of Congress’s Music Section of the Division for the Blind and Physically Handicapped available in 1976.

- National Institute for the Blind. The Braille Centenary. [London]: National Institute for the Blind, [1929]. Focuses on music.

- National Union of the Professional and Industrial Blind of Great Britain and Ireland. Report of Deputation of Musicians and Tuners to France and Germany. [London]: National Union of the Professional and Industrial Blind, 1930. Describes a research trip by delegates from the UK to France and Germany to explore best practice options for employing blind people as musicians and piano tuners.

- The New Braille Musician (1973 & 1975). Outlines services available to blind musicians in the 1970s.

- Ontario Institution for the Education of the Blind. Annual Reports, 1880. Toronto: Printed by C. Blackette Robinson, 1881. Includes a discussion of the types of music notation then available to blind musicians.

- Reuss, Alexander, Ellen Kerney, and Merle E. Frampton (trans). Development and Problems of Musical Notation for the Blind. [New York]: New York Institute for the Education of the Blind, 1935. Provides a short history on music notation for the blind.

- Sherman, Robert. “Why Popular Music for the Blind,” Outlook for the Blind 52, no. 3 (March 1958): 89-92. Article discussing when popular music is a good career choice for blind people

- Watson, Edward. The Blind Musician and His Training. [London]: National Institute for the Blind, 1922. A description of music education for the blind written in 1922.

- Wiener, William R., Richard L. Welsh, and Bruce B. Blasch. Foundations of Orientation and Mobility, Volume II, Instructional Strategies and Practical Applications. New York: AFB Press, 2013. The chapter on Improving the Use of Hearing for Orientation and Mobility is particularly relevant to this collection.

Music and Medicine

Music and Medicine

This section includes a range of references on music being used in therapy and rehabilitation, discussions of the ways music and sound can exacerbate medical and problems and articles on the health and wellbeing of musicians. Perhaps the most noticeable thing about this collection is the degree to which medical technologies and practices have changed over time. Early reports range from the dangerous, such as Dr. Andréas Wawruch’s use of lead to treat Beethoven on his deathbed in 1827, described in Rapport médical sur les derniers temps de la vie de Ludwig van Beethoven, to the downright bizarre, such as the claim that one patient experienced “blood jetted from the veins with considerable force” every time he heard a drum (p.484), written in Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine in 1898. However, even in this early volume we see scientists and doctors beginning to grapple with the effects that music has on the body, including descriptions of studies on the effect of music on respiration (p.486) and depression (p.487).

In Henry Addington Bruce’s 1919 volume Nerve Control and How to Gain It the descriptions of using music in mental health settings to influence mood and regulate emotions, while relatively simple, are much more familiar to modern audiences. By the 1990s, understandings of interactions between music, medicine and health were much more developed. In An Amateur Musical Group as a Factor in Solving the Tasks of Social Rehabilitation for Blind and Visually Impaired People, we learn about a program to use music ensembles to reduce social isolation in people with low vision. Meanwhile, Harvard Medical Alumni Bulletin – Music and Medicine Special Report includes articles that explore music and medicine from a range of angles, including music therapy for people rehabilitating from traumatic injury, research on the way the brain interprets sound as music, and treating injuries common to professional musicians.

- Bruce, H. Addington. Nerve Control and How to Gain It. New York and London: Funk & Wagnalls, 1919. Contains a chapter on music and health.

- Esquirol, Etienne, and E. K. Hunt (trans). Mental Maladies: Treatise on Insanity. Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1845. Includes conditions we would now call autism and intellectual disability. Has multiple sections on how music can be used to cause or cure mental illness.

- Gould, George M., and Walter L. Pyle. Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine: Being an Encyclopedic Collection of Rare and Extraordinary Cases and of the Most Striking Instances of Abnormality in All Branches of Medicine and Surgery, Derived from an Exhaustive Research of Medical Literature from Its Own Origin to the Present Day, Abstracted, Classified, Annotated, and Indexed. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1898. Pages 484 to 487 give theories on both the disabling and healing effects of music and other sounds.

- Harvard Medical Alumni Bulletin – Music and Medicine Special Report, 1999. This 1999 special edition of the Harvard Medical Alumni Bulletin includes a range of articles about music and medicine.

- Kantor, V.Z. “An Amateur Musical Group as a Factor in Solving the Tasks of Social Rehabilitation for Blind and Visually Impaired People,” in Urgent Problems of Social and Occupational Rehabilitation of the Visually Handicapped: Reports Presented at the International Conference on Blindness, Minsk, September 17-23, 1989. Minsk: Polmaya, 1991. A report on using music ensembles to combat social isolation in people with low vision.

- Wawruch, Andréas. “Rapport médical sur les derniers temps de la vie de Ludwig van Beethoven,” La Chronique Médicale: Revue Mensuelle de Médecine Historique, Littéraire & Anecdotique 34, no. 5 (May 1927): 144-149. Contains Dr. Andréas Wawruch’s account of Beethoven’s final days and medical treatments (in French).

Musicians with disabilities have always been at the forefront of technological and artistic change as they search for new technologies and techniques to support their diverse bodies and brains. Despite this, their contributions, and those of the teachers, therapists, composers and designers that work with them, is rarely highlighted in studies of music history. This collection begins to shine a light on this diverse community so that we can understand the techniques and technologies invented and utilised by disabled musicians in the past to better support disabled musicians of the future.