From Bauhin Caspar and Theodor de Bry’s Theatrum anatomicum (1605).

Primary Source Sets

MHL Collections

Reference Shelves

From Bauhin Caspar and Theodor de Bry’s Theatrum anatomicum (1605).

From Lady Caroline Catherine Wilkerson’s Weeds and wild flowers : their uses, legends, and literature (1858).

~This post courtesy Allen Smoot, UCSF Archives Intern.

Image from “The case against smokeless tobacco: five facts for the health professional to consider,” September 1980, page 4.

As an intern for the UCSF Archives, I’ve been working on digitized state medical society journals and tobacco control collections. At UCSF, the Archives and the Industry Documents Library both house immense collections of tobacco-related material. In the Industry Documents Library there are millions of documents from tobacco companies about their manufacturing, marketing, and scientific research. I narrowed in on chewing tobacco and how it became popular in the sporting world. Continue reading

Albert as a young man.

This post is courtesy Joan Thomas, Rare Books Cataloger at the Center for the History of Medicine at the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine of Harvard Medical School.

On December 14th, 1861, Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, husband of Queen Victoria, succumbed to a lingering illness that doctors diagnosed as typhoid fever. There has been speculation that Albert may in fact have died of Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis, both of which involve the debilitating stomach pain from which he suffered. In an article entitled, “The death of Albert Prince Consort: the case against typhoid fever” (QJM. 86 (12) 1993: 837–841), J.W. Paulley argues as follows:

“That he had been intermittently unwell with abdominal symptoms for several months before the terminal stage of his illness, only 9 days after this sensitive and vulnerable man was confronted by an intensely personal insult, lends further support to a diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease.”

Albert and Victoria.

The ”intensely personal insult” Paulley mentions was the Prince of Wales’ liaison with an Irish actress, Nellie Clifden, and the widespread rumors of blackmail and pregnancy. The stress resulting from such an embarrassing situation may have been the catalyst for the Albert’s final illness. Paulley concludes that “[s]ome patients with fulminating inflammatory bowel disease, if that is what the Prince had, decline such help, preferring to brood rather than speak, and take their bottled-up feelings of resentment to the grave.”

~This post courtesy Katie Healey and Caroline Lieffers, doctoral students in Yale’s Program for the History of Science and Medicine, with additions by Melissa Grafe, John R. Bumstead Librarian for Medical History, Head of the Medical Historical Library.

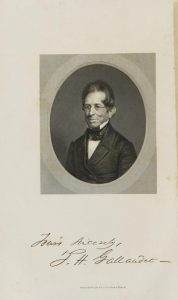

Portrait of Thomas H. Gallaudet (1787-1851). Gallaudet is shown here wearing glasses; his name in American Sign Language is the same as the sign for GLASSES. From Henry Barnard, A discourse in commemoration of the life, character, and services of the Rev. Thomas H. Gallaudet, LL. D. : delivered before the citizens of Hartford, Jan. 7th, 1852 : with an appendix containing history of deaf-mute instruction and institutions and other documents (Hartford: Brockett & Hutchison, 1852).

Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, instrumental in the establishment of the first permanent school for deaf children in the United States, was born on December 10th, 1787. The popular account of the school’s founding states that in 1814, the young Reverend Gallaudet wondered why the daughter of his Hartford neighbor did not laugh or play with his own younger siblings. Nine-year-old Alice Cogswell was deaf, and her family and friends struggled to communicate with her. Gallaudet traced the letters H-A-T into the dirt with a stick and pointed to his hat. Alice immediately understood, and Gallaudet realized his life’s calling. After observing different methods of instruction and communication on a European voyage supported by Alice’s father, Dr. Mason Fitch Cogswell (BA Yale 1780), Gallaudet concluded that the French method of sign language was most effective. He recruited Deaf Frenchman Laurent Clerc to help establish the Connecticut Asylum for the Education and Instruction of Deaf and Dumb Persons, which opened in Hartford on April 15, 1817. Alice Cogswell was its first registered student. Now called the American School for the Deaf, this historic institution will celebrate its bicentennial in 2017.

Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet earned his bachelor’s (1805) and master’s (1808) degrees at Yale before graduating from Andover Theological Seminary in 1814. Following his serendipitous encounter with Alice Cogswell, Gallaudet embarked on a year-long tour of European deaf schools. After a frustrating visit to the secretive Braidwood Academy in England, which taught speech and speechreading, he attended a demonstration of the French manual method—that is, sign language—in London. The National Institute of the Deaf in Paris invited Gallaudet to study French Sign Language and deaf instruction. Impressed with their curriculum, Gallaudet persuaded the esteemed instructor Laurent Clerc, a former student of the Institute, to teach deaf children in America. A commemoration of Gallaudet’s life was printed in 1852 and is available through the Medical Heritage Library partner National Library of Medicine.

Laurent Clerc was born in La Balme, France in 1785. As he later recounted in his autobiography, he fell into a fire as a toddler, which left him deafened and scarred his cheek. His name is signed by brushing the index and middle fingers twice down the cheek. Clerc was an exceptional student and later an internationally known instructor at the National Institute of the Deaf in Paris. He left his students only reluctantly in 1816, when Gallaudet persuaded him to come help American children. During the fifty-two-day voyage across the Atlantic, Clerc and Gallaudet exchanged lessons in French Sign Language and English, and Clerc kept a diary to practice his English. The Laurent Clerc papers (MS140) are available for research at Yale University’s Manuscripts and Archives, and the Mason Fitch Cogswell papers (GEN MSS 920) are at Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. Read an address on deaf education delivered by Clerc in 1818 through this online copy, provided by the Medical Heritage Library.

Title page from Laurent Clerc, An address, written by Mr. Clerc, and read by his request at a public examination of the pupils in the Connecticut Asylum : before the governour and both houses of the legislature, 28th May, 1818 (Hartford: Hudson & Co. Printers, 1818).

Gallaudet University in Washington D.C. was named Gallaudet College in 1894 in honor of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet. Founded in 1864, Gallaudet University is the world’s only liberal arts college specifically for the Deaf and hard of hearing. It remains a center of both Deaf culture and Deaf rights activism.

For more on Gallaudet and Deaf education and culture, make sure to visit, the online exhibition Deaf: Cultures and Communication, 1600 to the Present.

From Shirley Hibberd and F. Edward Hulme’s Familiar garden flowers (1879).

Who among us has not experienced the dreaded throb of cranial pain that accompanies stress and anxiety? Headaches seem to be the physiological manifestation of modern life’s tensions: perhaps more so than aches in any other part of the body, pain in the head symbolically ties together physical, mental, and emotional distresses.[1] In popular culture, headaches are also seen as a particularly female trait – think of the old misogynistic joke about a woman pleading a headache as an excuse to avoid a man’s sexual advances. While acting as humor on the basis of supposed female frailty and sexuality, the alleged headache functions to indicate the inner conflict the woman has between the different demands she faces because of her gender and her will as an individual. Managing these clashing societal demands and personal desires is, as it were, a headache.

In my reading of popular nineteenth-century American novels by women, I have noticed an emphasis on women’s headaches as an indicator of the stresses of the modernizing world. Headaches emerge as a recurring trope in these novels about women navigating new gender roles amidst changing ideas about women’s self-actualization both in the home and in the workplace. For instance, in Sara Payson Willis’s semi-autobiographical novel Ruth Hall: A Domestic Tale of the Present Time (1854), she chronicles her titular protagonist’s climb from poor widowhood to successful writer. A proxy for Willis, a.k.a. Fanny Fern, the highest-paid columnist in the United States, Ruth is plagued by headaches throughout the narrative. Elizabeth Stuart Phelps, known as the author of one of the great bestselling novels of the century, The Gates Ajar, also channeled her personal and professional frustrations in The Story of Avis (1877). Avis wants to be an artist, but the constraints of the domestic sphere force her to temper her ambitions. In both novels, the headache is a ubiquitous refrain at points of tension between these women’s private lives and the various public demands they face. But what relation did these headaches as metaphor have to contemporary medical understandings of the phenomena? How might nineteenth-century medical literature allow us to better understand these ongoing cultural stereotypes about women’s headaches?

I researched these questions at the Historical Medical Library of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia as a proud recipient of a travel research grant from the F.C. Wood Institute for the History of Medicine. Texts I hoped to investigate that are in the Library’s collection included both standard and homeopathic medical publications such as Treatise on Headaches: Their Various Causes, Prevention, and Curse (1855), Nervous Headache: For Medical Profession Only (1880), and Headache and Its Material Medica (1889).

Unexpected hazard of research: turns out that it can be a challenge for a modern reader like myself to resist sympathetic pangs of pain when you spend hours reading detailed medical descriptions of headaches! Often referred to as the “nervous headache,” the “sick headache,” and the now obsolete term “megrim,” the medical literature consistently links the phenomenon to imbalances and abnormalities – such as being a woman. I joke not! It is often a vague historical truism that “people were sexist back then,” but it can be paradigm-shifting to read the specifics of how credentialed, authoritative professionals actively engaged in pathologizing women’s existence.

Female susceptibility to headaches apparently had to do with everything from the nebulous affliction known as “hysteria,” to menstruation, to mental and emotional excesses, to excessive education and literacy. Henry G. Wright, MD, in his Headaches: Their Causes and Cures (1856) alleges that women tend toward headaches for reasons ranging from “over-nursing a child” to exertion from reading “the contents of the circulating library from sheer want of better employment.” As for male sufferers of headaches, doctors associated their pain with emasculating deviancy such as masturbation, sedentariness, and “nervous” traits of emotional disturbances and anxiety. According to James Mease, MD, in On the Causes, Cure, and Prevention of the Sick-Headache (1832), “This disease is the result of our advanced state of civilization, the increase of wealth and of enjoyments in the power of most people in this country, and, I may add, of the luxurious and enervating habits in which those in easy circumstances indulge.” Western civilization itself is feminized.

During my visit I also found other striking materials that indicate how the spread of medical knowledge grew with the further development of print technologies. There was a mass-produced pamphlet aimed at medical professionals that advertised a “nerve tonic” for headaches and other nervous ailments based on coca, known for its role in the drug cocaine. On Nervous or Sick-Headache (1873) by Peter Wallwork Latham, MD, included reproductions of colored plates that demonstrated the effect of severe headaches with aura on vision.

One thing that must be stressed: the women who were the subjects of these medical treatises were white and from the middle, if not upper, classes. The pain of poor women, women of color, and other marginalized groups did not merit the same medical attention and were sometimes not considered to exist. In his same text, Dr. Mease alleges that headaches are “unknown among the natives of our forests.”

Finally, I hope to put this discussion of women’s headaches into a broader conversation about pain in medicine. The generous time afforded to me by the F.C. Wood Institute grant enabled me to peruse many other research interests related to women and medical science. I went through materials related to J. Marion Sims, MD, considered the father of American gynecology. He built his career on developing surgeries to fix fistulas – by practising on enslaved black women. In his writings, there was no mention of their pain.

In 2015, the journal Pediatrics, published by the American Medical Association, highlighted an editorial that reviewed a broad range of scientific studies on racial discrimination and pain treatment in medicine from the 1970s onward. Perhaps the question for us should not only be what the causes and manifestations of pain are, but also whose pain gets recognized.

[1] For more on the history of pain and medicine in America, I recommend Martin Pernick’s A Calculus of Suffering.

~This post courtesy Beth Lander and Christine “Xine” Yao. Ms. Yao just earned her PhD in English at Cornell University. Later this year she will begin her position as a SSHRC Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of British Columbia. She received an F.C. Wood Institute Travel Grant from the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 2015.

From Anne Pratt’s Wild flowers Volume II (1893). Volume I is available here.

In honor of World AIDS Day (which was yesterday, yes.)

The Hopkins and the Great War exhibit features the stories of several women veterans of World War I . By exploring the experiences of the female Johns Hopkins doctors and nurses, the exhibit sheds light on the opportunities women had to serve during the war and the ways in which gendered norms varied by professional training and nationality. Continue reading