Delayed due to the holiday Monday (which we hope everyone who got it enjoyed).

From Carolina medical journal, volume 55 (1906).

Delayed due to the holiday Monday (which we hope everyone who got it enjoyed).

From Carolina medical journal, volume 55 (1906).

Please join us for the 13th J. Worth Estes, M.D. History of Medicine Lecture sponsored by the Boston Medical Library on Tuesday, May 23, 2017 – 5:30pm. To register, contact the Boston Medical Library at BostonMedLibr@gmail.com or 617-432-5169.

With the upcoming 50th anniversary of the first heart transplant operation, performed by South African surgeon Christiaan Barnard in December 1967, Prof. Shelley McKellar examines cardiac transplantation alongside the development of artificial hearts as replacement therapies for heart failure patients during the 1960s. Not long after Barnard, American surgeons Adrian Kantrowitz and Norman Shumway performed heart transplant operations in New York and California respectively. Within weeks, more cardiac surgeons jumped on the transplant ‘bandwagon.’

In the year 1968, more than 100 heart transplant operations were done worldwide, with Denton Cooley, Norman Shumway and Michael DeBakey performing the greatest number of cases. But patient mortality rates were appalling high due to organ rejection and infection. Still dying heart failure patients camped outside the offices of heart transplant surgeons, hoping for a life-saving procedure.

In 1969, Cooley implanted an artificial heart in a Houston man as a desperate measure to provide this. The device kept the patient alive for 64 hours until he received a donor heart, but this only sustained him for another 32 hours before the patient succumbed to pneumonia and kidney failure. The artificial heart implant case fueled the debate concerning the best cardiac replacement therapy—human or mechanical parts—to offer heart failure patients; neither produced satisfactory outcomes and many in the medical community questioned the continued pursuit of these treatments. (The 1969 implant case also severed the professional relationship of DeBakey and Cooley due to allegations of device theft and lack of authorization to perform the implant procedure.)

McKellar explores how the challenges and uncertainties experienced in heart transplant surgery augmented the standing and perceived value of artificial heart implantation as a complementary, not competing, cardiac replacement treatment in a period of ‘spare parts’ optimism in American medicine and society.

Prof. McKellar completed a PhD in the History of Medicine at the University of Toronto, under the supervision of Prof. Michael Bliss. She then worked at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC on a documentary history project before taking a tenure-track position in the Department of History at Western University, London, Canada in 2003. In 2012, she became the Hannah Chair in the History of Medicine at the Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry at Western University. In teaching medical students, she aims to get them to appreciate the historical and cultural contingency of medical practice – that is – recognize that time and place matter regarding what we think we know and how we practice medicine.

Prof. McKellar’s research focuses on the history of surgery, predominantly cardiac surgery, medical technology, and the material culture of medicine. Her newest book, entitled Artificial Hearts: The Allure and Ambivalence of a Controversial Medical Technology is forthcoming – this fall 2017 – with Johns Hopkins University Press. This book traces the history of an imperfect technology, situating the more-well-known events of the Michael DeBakey and Denton Cooley professional fall-out after the first artificial heart implant case in 1969 as well as the 1982-83 Jarvik-7 heart implant case of Barney Clark within a larger historical trajectory that also includes the development of atomic artificial hearts and ventricular assist devices (or ‘partial’ artificial hearts.) It can be seen as a case study that speaks to questions of ‘success,’ values, expectations, limitations, and uncertainty in a high-technology medical world that grapples with end-stage disease therapies.

McKellar has also written a biography of Toronto surgeon Gordon Murray who operated on the heart in the era of closed-intracardiac operations (before open-heart surgery), built the first Canadian artificial kidney machine, and pursued research on a controversial cancer serum and a spinal cord surgical procedure to restore function in paraplegics. McKellar also co-authored a book, entitled Medicine and Technology in Canada, 1900-1950, which was commissioned by the Canada Science and Technology Museum to assist in their mandate to collect and research medical technology.

As much as possible, McKellar incorporates medical objects into her teaching and research. As curator of the Medical Artifact Collection at Western, she conducts object research, mounts displays, and runs ‘hands-on’ student workshops to spotlight the often ‘hidden’ history of medical instruments and devices.

Cannon Room, Building C

Harvard Medical School

240 Longwood Avenue, Boston MA

To register, contact the Boston Medical Library at BostonMedLibr@gmail.com or 617-432-5169.

Exhibit opening and Archives talk: “DO THE BEST FOR OUR SOLDIERS:” University of California Medical Service in World War I.

Date: Tuesday, May 23rd

Exhibit Tour: 11 am – 11:45 am, main floor of the Library

Lecture: 12 pm – 1:15 pm, Lange Room, 5th Floor, UCSF Library

Exhibit Tour: 1:30 pm – 2 pm, main floor of the Library

Lecturers: Morton G. Rivo, DDS (retired) and Wen T. Shen, M.D. (UCSF)

Moderator: Aimee Medeiros, PhD (UCSF)

Location: Lange Room, 5th Floor, UCSF Library – Parnassus

530 Parnassus Ave, SF, CA 94143

This event is free and open to the public. Light refreshments will be provided.

REGISTRATION REQUIRED: http://calendars.library.ucsf.edu/event/3321575

Lieutenant Colonel Howard C. Naffziger in World War I army uniform. Base Hospital 30 collection, AR 2017-16, carton 1, Family Album World War I.

The UCSF Archives and Special Collections is pleased to announce the opening of a new exhibit at the UCSF Library, “DO THE BEST FOR OUR SOLDIERS:” University of California Medical Service in World War I. The exhibit commemorates the centennial anniversary of US involvement in World War I and recognizes the service of UCSF doctors, nurses and dentists at Base Hospital No. 30 in Royat, France. It also highlights the war-related research and care provided by UCSF scientists, clinicians, and healthcare workers in San Francisco and abroad.

Join UCSF Archives & Special Collections for guided tours of the exhibit and an afternoon talk with Drs. Morton G. Rivo and Wen T. Shen. Dr. Shen will speak on the biography of Dr. Howard C. Naffziger. Lieutenant Colonel Howard C. Naffziger, a prominent neurosurgeon before the war, served in the Army Medical Corps in France and at home, as Chief of the Neuro-Surgical Service at the U.S. Army Letterman General Hospital located in the Presidio. Naffziger became the Chair of the first Department of Neurosurgery at the University of California in 1947.

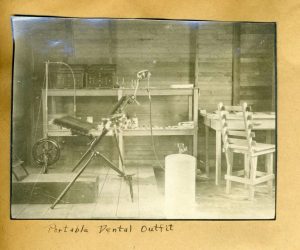

Dental chair and equipment. This picture accompanied aletter written to Dr. Guy S. Millberry on October 7, 1918. UCSF School of Dentistry scrapbook titled “Dental College Alumni Serving in the First World War, 1917 – 1919.”

This exhibit was curated by Cristina Nigro, graduate student from the History of Health Sciences Program, UCSF Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine.In April 1917, when America formally entered World War I, the United States Army had 86 dental officers, the US Navy, even fewer. Dr. Rivo will discuss the contributions of the UCSF Medical and Dental Schools that helped to quickly establish extensive dental/maxillofacial services on the Home Front and with the American Expeditionary Forces in France. He will address the role of dentists and oral surgeons, both in the US as the military mobilized, and in France, during the ensuing brutal year and a half of combat which terminated in November 1918.

Morton G. Rivo, DDS

Dr. Rivo received his dental education at SUNY Buffalo. He continued his specialty training in Philadelphia and Boston, first as a Fellow in Periodontology at the Graduate School of Medicine of the University of Pennsylvania and then as Resident Fellow in Periodontology and Oral Medicine at the Beth Israel-Deaconess Hospital in Boston. Dr. Rivo served as a Captain in the US Army Dental Corps in France, stationed near the old World War 1 battlefields.

After practicing for several years in Buffalo, Rivo transferred his clinical practice to San Francisco where he subsequently worked and taught periodontics for over 30 years. He is the former Chief of Periodontics at UCSF Medical Center/ Mt. Zion Hospital and was a member of the Medical Staff at California Pacific Medical Center. Dr. Rivo is past-president of the American Academy of the History of Dentistry. He is also the past-chair of the Achenbach Graphic Arts Council at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Dr. Rivo has retired from the practice of periodontology and currently is a student at the Fromm Institute at the University of San Francisco, where he is studying art, music, history and philosophy.

Operating room at Juilly, France in 1918 with Surgical Team #50, friends and Miss Perry Handley. UCSF Tales and Traditions, Volume VIII, Base Hospital 30 staff, WWI.

Wen Shen, M.D.

Wen T. Shen, M.D., M.A. is an endocrine surgeon specializing in procedures for thyroid, parathyroid and adrenal gland surgery. His research focuses on the molecular biology, genetics and treatment of thyroid cancer as well as the use of minimally invasive surgery. Shen also has an interest in medical history and has studied the development of hormonal therapies for benign and malignant conditions and the impact of the 1942 Coconut Grove Fire in Boston on the evolution of surface treatment for burns.

Dr. Shen graduated magna cum laude at Harvard College, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in history and science. He earned a medical degree and completed a surgical residency and research fellowship in endocrine surgery at UCSF. He received the Esther Nusz Achievement Award from the UCSF Department of Surgery, Resident’s Prize from the Pacific Coast Surgical Association, William Osler Medal from the American Association for the History of Medicine and Rothschild Prize from the Department of the History of Science at Harvard University.

In 2016, Dr. Shen was elected the 67th President of the UCSF Naffziger Surgical Society for its 2016-2017 term.

It’s grey and cold here in Boston today so lets have a nice bright flower to start the week off right.

From Shirley Hibberd and F. Edward Hulme’s Familiar garden flowers (1879).

On April 1st, the College of Physicians of Philadelphia released what we lovingly refer to as the “Digital Spine,” one of the few  catalogs in the United States that merges descriptions of, and access to, library, archival and museum collections.

catalogs in the United States that merges descriptions of, and access to, library, archival and museum collections.

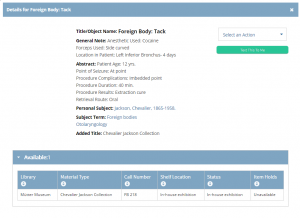

Approximately 145,000 bibliographic records for collections in the Historical Medical Library and approximately 28,000 records for objects in the Mütter Museum will be merged in a single, cross-searchable database. To sample this integration, go to https://cpp.ent.sirsi.net/client/en_US/library and search for “foreign bodies.”

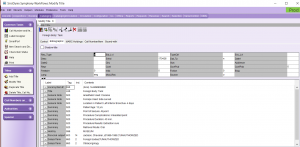

Museum records are slowly being released into the online public access catalog (OPAC). One of the biggest problems with integrating these two collections is the lack of standardization for describing museum objects (of any kind). In library description, we have “title.” In museum description, something akin to a title can be found in “Remarks” or “Description” or “Object Description” or “Object Name.” Building crosswalks between library and museum descriptions is an engaging activity.

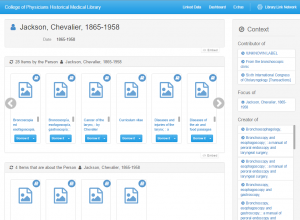

Another problem is the interim use of the MARC format to catalog museum objects. The long-term goal of the Digital Spine project is to expose collections metadata to crawling by search engines. In order to do this, we had to start with MARC, which seems antithetical, since MARC is not a structure that is understood by search engines. The College selected SirsiDynix as the vendor for this project because of SirsiDynix’ recent release of its BLUEcloud LSP. BLUEcloud Visibility pulls a library’s records and transforms them using BIBFRAME, which exposes catalog records as linked data. Here, for example, is part of the “Person” record for Chevalier L. Jackson, the “father” of American laryngology, whose foreign body collection, items referenced above, is one of the first museum collections to be released into the OPAC.

In the near future, we anticipating spending a lot of time tidying museum records and releasing them to the OPAC; retrospectively cataloging original library material that never made it into the original conversion to electronic format; and working with SirsiDynix to create an archives “module” to accommodate hierarchically described collections. In the long term, we plan to expand the reach of our metadata as linked data – how extensible can we be? In answering that question, we will truly free the LAMs from the silo.

You are cordially invited to attend a lecture by the distinguished historian and professor Dr. Margaret Humphreys titled “African Americans in Civil War Medicine”. Many histories have been written about medical care during the Civil War, but the participation and contributions of African Americans as nurses, surgeons, and hospital workers has often been overlooked. The event will be held on May 10, 2017 at 5:30 PM at the Knowledge Center of the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences located at 701 West 168 Street (Fort Washington Avenue) on the Columbia University Medical Center campus. Continue reading

From The Carolina Medical Journal (1900).

The Archives and Special Collections department of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Library, in collaboration with the San Francisco Public Library (SFPL) and the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender (GLBT) Historical Society, has been awarded a $315,000 implementation grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. The collaborating institutions will digitize about 127,000 pages from 49 archival collections related to the early days of the AIDS epidemic in the San Francisco Bay Area and make them widely accessible to the public online. In the process, collections whose components had been placed in different archives for various reasons will be digitally reunited, facilitating access for researchers outside the Bay Area. Continue reading

From Stanford Allen and Sons, Ltd., The romance of Empire drugs (undated).

~This post courtesy of Katie Healey and Caroline Lieffers, doctoral students in Yale’s Program for the History of Science and Medicine, with additions by Melissa Grafe, John R. Bumstead Librarian for Medical History, Head of the Medical Historical Library.

Title page of An Address in Behalf of the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb and the Blind by Edward M. Gallaudet, 1858.

In 1856, Amos Kendall, former postmaster general of the United States, became guardian to several deaf children. Concerned by their limited educational prospects, he donated two acres of his estate in the capital to establish the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb and Blind, to be run by Edward Miner Gallaudet. The blind students were soon moved to a separate school in Baltimore. Not satisfied with just secondary education, Kendall convinced Congress to grant the school the authority to award college degrees. In 1864, President Lincoln signed the college’s charter and President Grant signed the diplomas of its first graduates, establishing a tradition of presidential signatures that continues on its diplomas today. The college was renamed Gallaudet College in 1894, in honor of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, and became Gallaudet University in 1986. Continue reading