~This post is courtesy Polina Ilieva, UCSF Archivist.

This is a guest post by Aaron J. Jackson, PhD student, UCSF Department of Anthropology, History and Social Medicine.

One-hundred years ago, the First World War raged into its fourth year. Millions perished in the conflict as the armies of the “civilized” nations applied industrial efficiency to the brutality of warfare. The first weeks of conflict in 1914 shattered traditional conceptions of war. While battlefield success once depended on the ability to field more and better-trained men, the machines of the modern age leveled numerical and soldiery advantages. These new weapons wreaked death and destruction on unprecedented scales and forced the survivors to dig defensive trenchworks that quickly stretched from the Alps to the English Channel along Germany’s Western Front. A deadly stalemate ensued as opposing armies attempted to cross the no man’s land between the trenchworks, often suffering enormous losses in futile assaults. The war became one of attrition and soon caught civilians in its machinations as the richest economies in Europe quickly drained their resources into supplying the war machine.

The entry of the United States into the war in 1917 promised a glimmer of hope for the Allies that they would finally be able to overwhelm the Germans, but it would take time for the enormous resources of the unscathed Americans to be brought to bear. Meanwhile, the Russian collapse in March 1918 presented the German High Command with an opportunity to break the stalemate and deliver a knockout blow before the Americans could fully mobilize by shifting more than fifty divisions of troops from the Russian frontier to the Western Front. The Kaiserschacht, or Spring Offensive, would be the largest German assault of the entire war, with more than three million soldiers poised to break through the Allies’ lines and force a peace on German terms.

Figure 11 – Group photo, nurses and soldiers, World War I.

Meanwhile, the men and women of U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 30—the University of California School of Medicine Unit—arrived in France with the expectation of providing expert medical care to the soldiers wounded on the front lines. The hospital unit ostensibly formed before Congress officially declared war on April 6, 1917, and they spent more than a year gathering supplies and personnel, raising funds, navigating the Army bureaucracy, training in the latest medical techniques and military drills, and traveling to France where they expected to set up a hospital and get to “the work” of caring for the wounded. What they found in France, however, was the Herculean task of converting an ancient resort town in the Auvergne Mountains into a modern hospital.

This entry, the third of four planned posts, will cover “the work” of Base Hospital No. 30. After the arrival of the first patient train in June 1918, hospital personnel worked around the clock caring for thousands of sick and wounded soldiers—many of them surgical cases—right through the Armistice of November 11, 1918. These stories are derived primarily from materials kept at the UCSF Archives & Special Collections at the Parnassus Library in San Francisco, and it is with great appreciation to the archival staff there that I write about the experiences of the men and women of the University of California School of Medicine in the Great War. If you have not read them yet, please take a moment to read Part One: Organization, Mobilization, and Travel and Part Two: France for the context they provide.

Figure 12 – Fighting in Belleau Wood.

The German army began the Kaiserschlacht in March 1918 with a massive artillery barrage, dropping more than one million heavy shells on the Allies’ trenches followed closely by lightning-fast stormtrooper assaults to break through opposing lines and create gaps that could be exploited and held by masses of infantry. This strategy allowed the Germans to break the stalemate that had dominated the Western Front since late 1914 and gain ground. They repeated their process in five separate assaults between March and July, gaining enough ground to put Paris under threat.

By June, as the offensive approached the Marne River, American troops including elements of the U.S. Marine Corps rushed to form defensive lines to hold back the Kaiser’s troops at Belleau Wood near Chateau-Thierry. As the Marines dug hasty defensive positions, retreating French troops warned them of the coming Germans and encouraged the Marines to fall back to better ground.

“Retreat? Hell! We just got here!” replied Captain Lloyd W. Williams of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines. Fighting from hastily-dug, shallow fighting positions, the Marines took advantage of an 800-yard long wheat field and their training as expert riflemen to halt the German advance and force the Kaiser’s forward elements to dig their own defensive positions in Belleau Wood and the nearby town of Bouresches. Having stalled the Germans, the Americans knew that they had to counterattack before the Germans could dig in too far.

On the morning of June 6, 1918, the Marines charged across the knee-high wheat fields separating them from the entrenched Germans. As they ran, German machineguns opened up, cutting down the charging Americans like the wheat through which they ran. German artillery rained down on the Marines with the high explosive shells shaking the ground and shattering bodies. Despite heavy losses, the Marines managed to reach the edge of the woods and the outskirts of Bouresches before their assault finally stalled, but they paid a heavy price. It was the costliest single day of fighting in the history of the Marine Corps to that date as 228 men gave up their lives and another 859 suffered wounds. And the fighting was far from over.

Over the subsequent twenty days, the Marines fought so fiercely to dislodge the Germans from Belleau Wood that they earned the nickname Teufel Hunden or “Devil Dogs” from their German opponents. The fighting was often hand-to-hand with artillery splintering the trees and filling the air with deadly wooden splinters in addition to shrapnel. Desperate to halt the American advance, the Germans deployed mustard gas, a chemical weapon that painfully blisters the skin, burns the eyes resulting in blindness, and inflames the lungs making breathing impossible if inhaled. As many as 2,000 Marines fell victim to the gas. By June 26, when the Marines finally secured Belleau Wood, they had suffered 1,811 killed and 7,966 wounded.

Figure 13 – Evacuating the Wounded.

The wounded began a journey through a tiered system of medical care established by the Army. The first stage consisted of regimental aid stations located just behind the front lines. Those who were able to do so walked to these stations while stretcher bearers carried the rest. Medical corpsmen and the occasional doctor would dress their wounds, send superficial cases back to the front lines, and coordinate the evacuation of the seriously wounded by motorized ambulance to the clearing stations and field hospitals located further behind the lines.

The field hospitals and clearing stations, while out of range of small arms fire, were often still within range of enemy artillery and aircraft. Despite these hazards, teams of nurses, doctors, and surgeons worked to stabilize their patients, clean their wounds, and prepare them for evacuation to the base hospitals located well out of danger. It was at these facilities that nurses would flush the eyes of gas attack victims with saline solution and surgeons would perform emergency surgeries under extreme conditions, often lacking proper supplies. The wounded who could be stabilized enough for the trip would then be loaded onto hospital trains for the journey to base hospitals like Base Hospital Thirty at Royat, five-hundred kilometers away from the front at Chateau-Thierry.

Figure 14 – The Hospital Trains.

When the first hospital train arrived at Base Hospital No. 30 on June 12, 1918, the hospital was not yet operational as the main kitchen installation was incomplete. Thankfully, the 360 patients aboard that first train were primarily convalescents who were able to help complete the preparations in time for the second train’s arrival on June 17. This second train held 461 seriously wounded patients from the fighting near Belleau Wood. Captain Earnest H. Falconer, Medical Corps (MC), described the scene for posterity in the pages of The Record:

On June 17 a train arrived in two sections, containing many gas cases…. These cases had been gassed on June 14. Many of them had severe skin burns, some comprising as much as one-eighth to one-half the total skin surface. In the more superficial burns the skin was a dusky purplish to reddish purple hue. The deeper burns were pale, translucent, edematous, with many blisters. In most cases serum was drained from blisters. The serum from these blisters was very irritating to the skin of the hands of the dressers, causing in some cases a mild dermatitis to be set up…. Nearly all these cases had burns on the scrotum and penis, which were painful and very slow healing. Also nearly all the cases had burns of the lids and conjunctiva, with occasional burns of the face and scalp. Many cases of bronchopneumonia were already present when the patients were admitted, and a number of these cases developed shortly after admission. These cases were nearly all fatal…. The cases with superficial burns healed for the most part very slowly. New skin formation progressed slowly, and the crusts that formed invariably contained pus beneath them.

Base Hospital Thirty consisted of 25 officers (all physicians), 65 nurses, and about 150 enlisted corpsmen. By June 18, they were treating 821 wounded soldiers, many requiring extra attention due to the nature of their injuries. The staff worked continually performing surgery, cleaning wounds, and feeding the patients, all the while continuing their efforts to improve the hospital’s infrastructure. Thankfully, the surgical cases in the first two trains were less taxing because their wounds had been debrided of foreign objects and dead and damaged tissue at the clearing stations and field hospitals. Amputations were dressed but kept open, allowing hospital staff to manage the healing process and maintain an aseptic wound environment. This was achieved through the Carrel-Dakin method, which involved applying diluted chlorine and bleach solution to wounds and dressings to prevent infections. It must have been an excruciating experience for the patients, but it worked to prevent deadly infections in the era before antibiotics.

Unfortunately, not all patients arrived in similarly good conditions. A train on August 21 contained men who had been kept in the clearing stations as medical professionals attempted to stabilize them enough for travel. They arrived with infected wounds requiring extensive debridement, additional surgery, and the occasional re-amputation of a limb to establish aseptic wound environments.

After the arrival of the first trains in June, hospital staff worked around the clock for months on end. Patient trains would arrive, usually and preferably with some notice, and the wounded would be carried by stretcher into the hospital and sorted. Surgical teams worked continuously, often without the aid of the x-ray machines for a want of electric power. The laboratory was similarly handicapped, making diagnosis and treatment that much harder for physicians. Nurses worked tirelessly to clean wounds, dole out medications, fill out charts, and keep a clean and ventilated environment. Corpsmen carried patients up several flights of stairs to their rooms, hauled water in buckets for want of proper plumbing, cooked meals in the kitchens and delivered them to non-ambulatory patients’ rooms, removed waste from the rooms, made new batches of Carrel-Dakin solution, worked to improve the plumbing and heating in the old hotels, loaded and unloaded hospital and supply trains, and somehow found a way to help keep the streets of Royat clean and the hotel cesspools from overflowing. There was so much work that ambulatory patients were conscripted to assist. And just when the hospital appeared to find its rhythm, events found a way to throw it off.

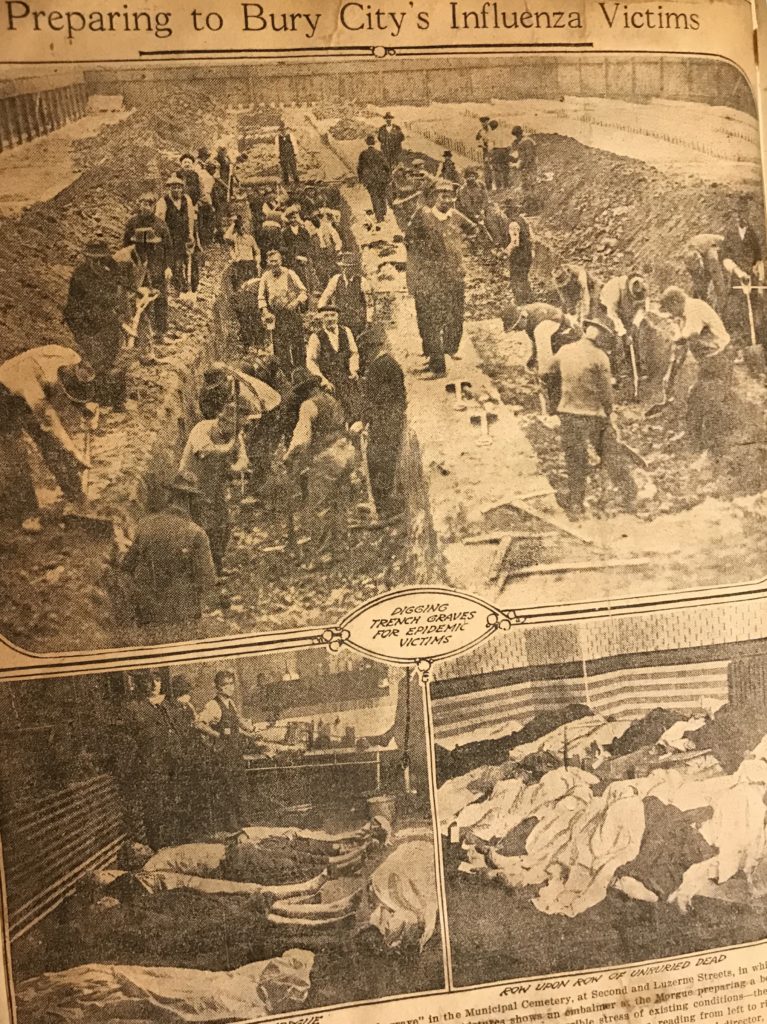

Figure 15 – The Influenza Pandemic of 1918.

On September 22, 1918, when the hospital was near full capacity, a train full of French patients arrived in the middle of the night without prior notice. Due to the hour, the hospital staff decided that the best course of action was to distribute the new patients throughout the hospital wherever a spare bed could be found. Unfortunately, they discovered that practically all the new patients were suffering from acute respiratory infection. Distributing them through the hospital into crowded rooms exposed other patients as well as the staff to infection.

By the end of September, as many as 40 of the 150 enlisted men assigned to Base Hospital No. 30 had to be hospitalized themselves, and many officers and nurses were also afflicted to a milder degree. Five corpsmen and one officer died from their infections, and as the epidemic spread among neighboring units, the hospital’s local admissions amounted to between 30 and 70 new patients a day. Making matters more difficult, the hospital’s laboratory officer and his assistants fell ill, necessitating a suspension of investigative work on the mysterious disease. Autopsies of the first victims indicated the cause of death to be pneumonia developed as a complication following a likely infection of influenza. The hospital staff could do little to combat the contagious disease other than to reorganize the patients to attempt to hinder its spread.

While Base Hospital Thirty dealt with its share of the Influenza Pandemic of 1918, they received orders to expand the hospital to accommodate anticipated casualties from the ongoing Allied counteroffensive. The Germans’ kaiserschlacht floundered in July and the Allies, their numbers and supplies flush with fresh American troops and materiel, had been pushing the Germans back ever since. Base Hospital No. 30 officers examined potential sites for expansion in Royat and completed leases for new buildings in September. They established another surgical unit and moved their administrative offices into the Royat Palace Hotel on September 26. The new buildings allowed them to finally abandon the old “dungeon” kitchen in the Continental hotel and create a new kitchen in the Grand Hotel, which did not have the Continental’s cesspool problems. The new space also allowed for the creation of a dedicated ward for respiratory and enteric cases, freeing up space in the already-established portions of the hospital for surgical and bed-ridden patients.

Figure 16 – Patient wards at Base Hospital No. 30 in Royat, France, 1918-1919.

The hospital also expanded beyond adding new wards. Corpsmen built warehouses near the rail head to ease the burdens of transferring supplies and coal bunkers to provide a consistent fuel supply for heating the hospital as the days and nights grew colder. The Army assigned more corpsmen to the hospital staff, and the officers organized a small local labor force to help keep up with waste, garbage, and maintenance concerns. Perhaps the most welcome addition to the hospital’s roster was a section of Army engineers to finally improve the hospital’s water, sewer, and electrical supplies. Corpsmen would no longer have to haul buckets of water up stairs or worry about overflowing cesspools, allowing them to do the work for which they trained, and there was plenty of that to go around. By the end of September 1918, Base Hospital No. 30 had roughly 30 physicians, 60 nurses, and 250 corpsmen to take care of a 2,400-bed facility, and the combination of the war and pandemic ensured that the hospital continued to operate near capacity. Beyond the work in Royat, the UC Medical School unit also contributed surgical teams to support the effort of stabilizing the wounded near the front lines. Two such teams, each consisting of two surgeons, two nurses, and three corpsmen, set out for the front lines to work in field hospitals to provide surgical intervention to wounded men, often within only a few hours of their injuries.

Figure 17 – Members of Surgical Team 50: Weeks, Woolsey, Dunn & Ireland.

Surgical Team No. 50 was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Alanson Weeks, who once played fullback for the undefeated 1898 Michigan Wolverines before moving to San Francisco to become a surgeon. Alongside Captain John Homer Woolsey, Nurses Agnes Dunn and Alta Ireland, and three enlisted men, Weeks set out for the front lines on June 6, 1918. The team arrived at the American Red Cross Hospital at Juilly (today on the northeast outskirts of Paris) at 3 p.m. on the 7th and his team was immediately assigned to an operating room and remained in surgery until 8 o’clock the following morning. Dr. Weeks recalled the experiences of the team’s time at Juilly in The Record:

The wounds were very severe in type, many fractures and a high percentage were infected with “gas” bacilli. There were also 300 “gassed” cases who were first treated at this hospital. The sight of these gassed men, lying on stretchers and filling the entire courtyard—blinded, hacking, begging for water, for protection from the sunlight for their sensitive eyes, and for something to relieve their pain—gave all of us a craving desire to meet the Hun and kill. June 16 saw the end of this tremendous rush of wounded…. The Team operated for the most part at night and during its watch cared for all neurological cases and approximately a total of 240 wounded.

Surgical Team Fifty specialized in neurological cases, of which there were many. Due to the nature of trench warfare, headwounds were frighteningly common as the soldier’s head was usually the only part of his body exposed to enemy fire. But like all surgical teams, No. 50 dealt with all types of cases as they came in, often without much notice. Victims of gunshots, artillery shrapnel, high explosive shock, chemical weapons, and even bayonet wounds were common sights, and the work kept coming. The seventeen-hour shift the team worked on its first day at Juilly would become routine until the team returned to Base Hospital Thirty in late October.

Before Surgical Team No. 50 could return, Base Hospital No. 30 sent out another surgical team, No. 51, under the command of Major Herbert S. Thomson on September 10 to support the evacuation hospital at Toul, near Nancy to support the St. Mihiel offensive. Accompanying Dr. Thomson was Captain Homer C. Seaver, who had graduated from the University of California Medical School only weeks before deploying to France, along with nurses Adelaide Brown and Kathleen Fores and three corpsmen.

Shortly after arriving at Toul, Surgical Team Fifty-One was put to work and faced similar working conditions to their predecessors, working seventeen out of the first twenty-four hours. They only saw the most serious cases and had no opportunity to follow up on their patients. As soon as they finished working to stabilize one patient, orderlies would take him off the table and another patient would take his place. The pace of work and long days coincided with the military offensives as the team worked sixteen- or seventeen-hour shifts for a week during the St. Mihiel offensive. During the space between assaults, the teams often found themselves traveling to a new front to support a new offensive.

Imagine graduating medical school and within a matter of weeks finding yourself working 16-hour days, seven days a week, doing nothing but intensive surgery on the most severe trauma cases imaginable and not being able to follow up on the results of your work because there are so many patients waiting—and literally dying in the process—for you to save their life. Such was the medical residency of Dr. Homer C. Seaver.

Figure 18 – The Meuse-Argonne Offensive, September 26 – November 11, 1918.

In October, Surgical Team No. 51 received orders to support the offensive into the Argonne Forest. The fighting there resembled Belleau Wood. The Germans had been beating a slow retreat since June, but now that their homeland was imperiled for the first time of the war, they turned and fought hard. In his account of the event for The Record, Major Thomson described the work in the Argonne:

We were ordered from Toul to the Argonne Forest on October 8 and received transportation by ambulances to Evacuation Hospital No. 14, situated in the Argonne Forest near the village of Les Islettes. This hospital was situated in the heart of the Argonne Forest near the line of American advance and in a country that had been completely destroyed by the Germans in their former campaign. The hospital was entirely under canvas except for a small chateau which housed the nurses and senior officers. This country was very wet; it rained nearly every day and there was mud everywhere. The operating tent was pitched on the ground and for the first few days there was considerable mud on the operating room floor. In order to go from the operating room to the wards, one had to wade through about six or eight inches of mud. While at Les Islettes, the Team was busy all the time, working on the twelve-hour shift. There never was a time when anyone had a breathing spell as the triage was always filled with patients and there was frequently a line of ambulances waiting in the road. At this hospital, only the seriously wounded were treated and there was a very large number of gas infections. Many times, patients were brought in from two or three days after being wounded and a patient was rarely operated on within 15 hours of being wounded. At this hospital, we were near the German lines and were treated to the spectacle of anti-aircraft guns shooting at the German planes and could always see the observation balloons over the forest to the north. It was difficult to get supplies in this region and the hospital was rather poorly equipped. On the 25th of October the Team was ordered to return to Base Hospital Thirty.

Thus, the work of Base Hospital No. 30 continued throughout the long months from June to November 1918. Their commemorative book The Record demonstrates just how busy “the work of the hospital” really was by its absences more than its inclusions. The pages of The Record are filled with pictures from the hospital unit’s early days of organization, its travels to France, and its struggles to transform a resort town into a modern hospital. But it only includes a few pictures of “the work.” Perhaps this absence is due to the fact that everyone was too busy caring for their charges to be able to take pictures or jot down notes for posterity. Or perhaps the absence marks a time in the history of Base Hospital No. 30 that needed no commemoration in something like The Record because those who were there remember it well. Perhaps both possibilities are true.

Figure 19 – Armistice Declared, November 11, 1918.

Regardless, when the Armistice went into effect on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month, and while the world breathed a sigh of relief at the end of the fighting, “the work of the hospital” at Base Hospital No. 30 and other hospitals throughout Europe and the United States continued at a frantic pace. For weeks, wounded men would continue to pour in to Royat.

This concludes Part Three: The Work of the Hospital. One part yet remains in the tale of the remarkable men and women of Base Hospital Thirty. In the final part of this series, we will take a closer look at some of the remarkable people who carried out that work, how they came home again, and what happened to them after the war.

In the meantime, I want to take the opportunity to encourage you to take a moment and visit the collection at the University of California San Francisco’s Parnassus Library in the Archives and Special Collections to read more about the incredible men and women who made up the University of California Medical School Unit in the First World War.

Figures:

11 – “Group photo, nurses and soldiers, World War I,” circa 1917, Mount Zion Photo Collection: Historical Life, UC San Francisco, Library, UCSF Medical Center at Mount Zion Archives, Calisphere, https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/c8028ttx/, accessed July 29, 2018.

12 – Georges Scott, “American Marines in Belleau Wood,” circa 1918, Illustrations, Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Scott_Belleau_Wood.jpg, accessed July 29, 2018; and George Matthews Harding, “Rounding Up German Prisoners,” July 1, 1918, War Department AF.25747, Smithsonian National Museum of American History, http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_448013, accessed July 29, 2018.

13 – Wallace Morgan, “U.S. Medical Officers,” circa 1918, War Department AF.25791, Smithsonian, http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_448030, accessed July 29, 2018; George Matthews Harding, “First Aid Station with American Wounded,” circa 1918, War Department AF.25742, Smithsonian Museum of American History, http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_448015, accessed July 29, 2018; and Wallace Morgan, “Dressing Station in Ruined Farm,” July 19, 1918, War Department AF.25767, Smithsonian Museum of American History, http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_448052, accessed July 29, 2018.

14 – “Loading and unloading patients during World War I,” circa 1917-1919, Base Hospital #30 Collection, UC San Francisco, Library, University Archives, Calisphere, https://calisphere.org/item/d3c4b7a0-ec00-4a29-99bf-b3157799718a/, accessed July 29, 2018.

15 – “The influenza ward at Walter Reed Hospital during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918,” and “St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps personnel wear masks as they hold stretchers next to ambulances in preparation for victims of the influenza epidemic in October 1918,” Library of Congress.

16 – “Surgical ward, an average size room, Hotel Metropole,” circa 1918, Base Hospital #30 Collection, UC San Francisco Library, University Archives, Calisphere, https://calisphere.org/item/ad3fa9c8-8d7e-4068-917f-47c7e4217154, accessed July 29, 2018; and “Surgical ward, German war prisoners, Royat Palace,” circa 1918, Base Hospital #30 Collection, UC San Francisco Library, University Archives, Calisphere, https://calisphere.org/item/69deaae8-23af-4dd4-8092-19237319153d, accessed July 29, 2018.

17 – “Alanson Weeks in uniform,” circa 1917-1919, Woolsey (John Homer) Papers, UC San Francisco Library, Special Collections, https://calisphere.org/item/5d2ca217-a521-4573-b693-0610c6019ac3, accessed July 30, 2018; “John Homer Woolsey in uniform,” circa 1917-1919, Woolsey (John Homer) Papers, UC San Francisco Library, Special Collections, https://calisphere.org/item/ceae074e-bff0-42a2-890b-b819e0480062, accessed July 30, 2018; and “Misses Dunn and Ireland leaving Clermont-Ferrand,” 1918, Woolsey (John Homer) Papers, UC San Francisco Library, Special Collections, https://calisphere.org/item/f187f041-1911-4aa9-aa26-be3a96d813aa, accessed July 30, 2018.

18 – “Soldiers of Headquarters Company, 23rd Infantry Regiment, 2nd Infantry Division, firing a 37mm gun during the Meuse-Argonne offensive,” 1918, U.S. Army Photo; Lester G. Hornby, “Argonne-Meuse 1918,” 1918, US Army Art Collection.