~Kelly Hacker Jones.

Following the “animal turn” in historical research, more work has been done in the history of medicine on animals as research subjects. In the realm of vaccination, this history should be immediately apparent: it’s right there in the name. Edward Jenner in his 1798 treatise, An Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccinae, applied a Latin name to the cowpox: variolae vaccinae (smallpox + from cows), from which the noun “vaccination” is derived. Jenner developed the first vaccine against a disease after observing that dairymaids and farm hands who had contracted cowpox from livestock were not susceptible either to smallpox infection or inoculation. Jenner’s innovation, as those familiar with the story know, was not greeted with universal enthusiasm.

Image 1: harvesting cowpox lymph from a calf for use in smallpox vaccine. Source: J. Aitchbee, What is Vaccine Lymph? Kilmarnock, Scotland: Joseph Scott, 1904, p. 6

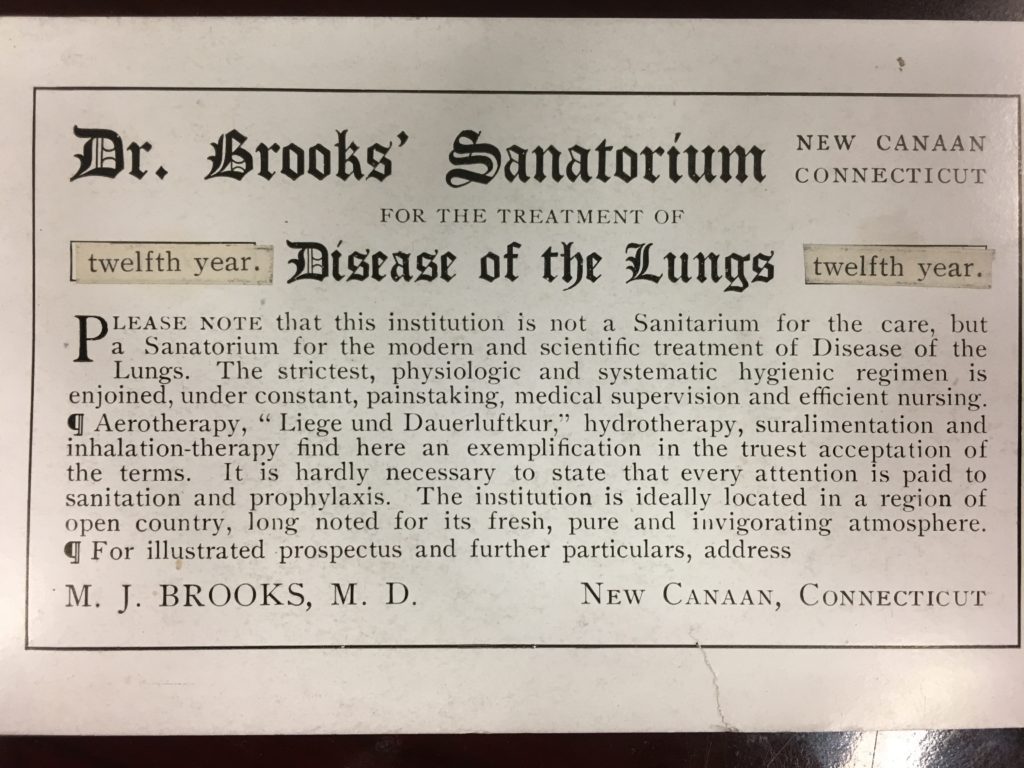

For one thing, just because a substance prevented deadly disease did not make all individuals wild about having it injected into their bodies. The author of “What is Vaccine Lymph?” certainly thought lymph collected from live cows was not suitable for human use. Referencing illustrations from a government report on the process of vaccine collection (see above), he explained that 18-month-old calves were walked alongside a rotating table, strapped to it, and then elevated into a horizontal position. This position and the restraints made it easier for the cultivators to inflict small cuts and rub cowpox matter into them, encouraging more cowpox sores to grow, and later harvested the lymph for use as smallpox vaccine. Once the cow had recovered from its cultivated cowpox, it was, according to this author, sold to the slaughterhouse.

In all likelihood, the original intent of the photographer was to reassure officials that the vaccine was collected in a regimented manner, but the photos were spun differently by Aitchbee.

The reader was expected to conclude that cultivating vaccine lymph was not only cruel to animals, but that the matter potentially contained the germs of other diseases, such as tuberculosis – cows were also a vector for that terrible disease – and thus posed a danger to human health. Visions of filthy stockyards and the sickly cattle from which vaccine lymph was harvested abound in anti-vaccination literature. One critic argued that inoculation with “puss,” whether from animals or humans, was unnatural and compulsory vaccination, therefore, constituted “assault and a crime in the nature of rape.”

Unsurprisingly, there was a great amount of overlap between anti-vivisectionist societies and anti-vaccination societies in the early twentieth century.

Contrast with this, the story of the diphtheria antitoxin. Whereas Jenner’s discovery took advantage of knowledge from farmers confirmed through his own clinical experiments and observations, the diphtheria antitoxin was developed in laboratories in France and Germany, using then-cutting-edge scientific techniques. As the antitoxin must be generated in an animal body, horses were used as they produce large quantities of blood and generate a fairly quick immune response to the antibodies (for a short history of the New York City Health Department’s diphtheria antitoxin farm, click here).

The antitoxin’s equine origin was not hidden from the public: newspapers coverage from 1895 included photographs of horses standing patiently, allowing their blood to be collected for use in serums that would save the lives of sick children.

Image 2: preparing a horse to harvest diphtheria antibodies for use in manufacturing antitoxin. Source: The Preparation of Diphtheria Antitoxin and Prophylactics (film), produced by G.B. Instructional Ltd., 1945.

Western cultural perceptions of horses as opposed to cows – horses are beautiful and dignified and cows are clumsy and well, unintelligent (I personally do not endorse either of those positions) – may have had an influence on how the public reacted to news that the latest vaccine on the market was also cultivated in animals. Portrayals of horses nobly giving their blood for the sake of innocent children would have gone a long way towards assuaging any qualms about their use as cultivators. Adding to the image of valued service, these horses, once they had given several serum donations, were retired to rural pastures.

Anti-vaccinationists still referenced cultivation in animals generally, but illustrated anti-vaccination sources in the MHL collections only use images of cattle for the purpose of discomforting the reader.

A 1945 educational film produced in collaboration with the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratories gave audiences a first-hand look at the conditions in which horses were kept during the process of cultivating and harvesting diphtheria antitoxin. The horse was led into a clean tiled room, the site for injections and blood draws was scrubbed and sterilized, and the veterinarians and technicians wore surgical scrubs. The horse is removed from the barnyard and becomes part of the laboratory (I will caution you that the film is overall horrendously dull, as one might expect from a 1940s-era educational film).*

Image 3: Vaccinating a sheep against anthrax. Two men working together in this method could immunize up to 150 sheep in an hour, assuming the remaining 149 stood still after watching this procedure. Source: George Fleming, Pasteur and His Work, from an Agricultural and Veterinary Point of View (London: William Clowes and Sons, 1886), p. 51.

So far I have highlighted the history of perceptions of the use of animals in the production of vaccines, but what about the effects of vaccines on animals themselves? As both vectors and victims of contagious diseases, animals have been recipients of vaccines to prevent illnesses such as rabies, anthrax, and distemper. Agriculturalists early realized the potential benefits to humans from vaccinating livestock: herds would live longer, healthier lives and produce more young.

Agricultural and veterinary historians have no doubt included vaccines in their accounts of the development of modern animal husbandry, but how have human and animal health alike been affected by vaccines? While the usual metaphor of the two-way street is an overstatement, given greater human agency, these sources indicate an inter-relationship between humans and the animals we’ve vaccinated.

*For more on mass media and its effects on popular perception of medicine, see Bert Hansen, Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio (Rutgers University Press, 2009).