~Rachael Gillibrand, MHL Jaipreet Virdi Fellow for Disability Studies, 2021

According to the World Health Organisation, at least 2.2 billion people around the world have some kind of visual impairment. These impairments are classified by the ‘International Classification of Diseases 11’ into distance vision impairments (sub-categorised into: Mild, Moderate, Severe, and Blindness) and and near presenting vision impairments. Today, many of these conditions can be treated relatively cheaply through the use of spectacles or contact lenses.

This primary source set will be divided into three main parts – each considering a different kind of technology used by individuals with ocular impairments. To begin with, it will discuss the development and use of spectacles – arguably the most ubiquitous of ocular technologies in the modern world. Then it will move on to discuss guide dogs, asking whether a living creature can even be labelled as a ‘technology’. Finally, it will discuss a range of reading technologies marketed throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Spectacles

Spectacles

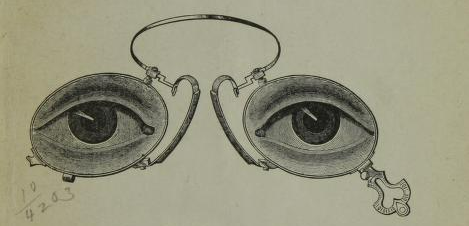

According to projections from the Vision Council, around 164 million American adults wear spectacles! In fact, of all the devices included in these ‘Disability and Technology’ source sets, spectacles (or glasses) are arguably one of the most ubiquitous forms of assistive technologies. As such, there is a huge amount of information pertaining to their construction, use and dangers, in the Medical Heritage Library’s collections.

However, the use of spectacles has a much longer tradition than most people realise. As Horner points out in his On Spectacles: Their History and Their Uses, magnifying lenses have been used as ocular aids since the ancient period. To demonstrate this, he cites Lanyard’s discovery of the Nimrud Lens, dating from 750 BC – 710 BC, as one of the earliest examples (this item is now held in the British Library and can be accessed here). However, it was not until the late thirteenth century, in Italy, that spectacles, as we might recognise them today, were invented.

The first textual reference to spectacles (discussed by George H. Oliver in his Address on the History of the Invention and Discovery of Spectacles) comes from the sermon of an Italian Friar named Giordano da Rivalto, delivered on February 23rd,1305. In this semon, Giordano stated that: ‘It is barely twenty years since the art of making spectacles which enable us to see better was introduced, one of the most useful arts in the world. I have myself seen and spoken to the man who first made them’ – but he does not reveal who this man might be. After this point, the demand for, and accessibility of, spectacles developed exponentially – resulting in the wide use of these items that we see today.

Prescribing Spectacles

Prescribing Spectacles

Most of the material we hold in the Medical Heritage Library, which pertains to spectacles, focusses on their construction, purchase and use from the nineteenth century onwards.

We see in the collections, a number of texts designed for opticians, medical professionals, and medical students, which outline how one ought to choose and prescribe spectacles for a patient. A good example of this can be seen in Robert Brudenell Carter’s series of lectures on Defects of Vision which are Remediable by Optical Appliances. These lectures, which were delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons in 1877, considered a range of conditions (including presbyopia, hypermetropia and myopia, astigmatism, and asthenopia), before assessing what sorts of spectacle lenses should be prescribed to treat them. In the case of presbyopia (the loss of the eye’s ability to focus on nearby objects, which is so frequently associated with ageing), Carter recommends the prescription of a range of concave lenses with gradually increasing magnifying powers to be used as an individual’s sight worsens. Very similar works, concerning these same ocular impairments, were produced by doctors such as D. B. St. John Roosa in 1899 and Archibald Stanley Percival in 1910.

Outside of these doctors and opticians writing for others within the medical profession, some medical professionals produced pamphlets for a public audience, which sought to advertise and educate people on the value of spectacles. For example, in 1856, F. A. Moschzisker produced Spectacles: Why and When to Use Them. This pamphlet which he ‘wrote to be read and in a very short space of time’, berates those ageing individuals who stubbornly refuse to wear spectacles, stating that: ‘The presbyopic Eye, if refused assistance, is necessarily strained by every attempt to perceive near objects, and suffers more in a few months by forced exertion than it would do in as many years, if assisted by such Glasses as would render vision easy and agreeable’.

Dangers of Using Spectacles

Dangers of Using Spectacles

Throughout the nineteenth-century, there began to emerge a market for quacks selling cheap, mass-produced spectacles. These concerned contemporary opticians who believed that, at best, these items were made of ‘common window glass’ and so did nothing to improve one’s vision and, at worst, these items were inappropriately polished and over strong, thereby causing damage to the eyes. For example, in his The Art of Preserving the Sight (1815), Georg Josef Berg dedicates a whole chapter to the ‘Inconveniences and Dangers of the Common Kind of Spectacles’, in which he argues that cheap and irregularly made spectacles can generate dark spots and callosities in the eye, resulting in minute dark shapes floating in one’s field of vision. Similarly, in his 1850 Spectacles: Their Uses and Abuses, Jules Sichel suggests that myodesopsia (floating shapes within one’s vision) is caused by the use of concave lenses with too strong a prescription for their user.

As a result of these concerns over the dangers associated with using inappropriate spectacles, several doctors offered advice on how take care of one’s eyes (in order to delay the use of spectacles for as long as possible), before then explaining how to select appropriate spectacles when their use was no longer unavoidable. A good example of this can be seen in John Harrison Curtis’s Observations on the Preservation of Sight, and on the Use, Abuse, and Choice of Spectacles (1834). In this text, Harrison Curtis draws attention to a whole host of ‘evils’ that can damage one’s sight. These include, the wearing of veils; white washed walls – especially when opposite a window and therefore reflecting the sun’s rays; poor hygiene; gazing on the moon; reading or practising needlework at night; overheating the blood through arguments or debates; and fatigue (to jame just a few!) He goes on to suggest that, if one avoids all of these things and still requires spectacles, these should be used ‘as sparingly as possible—only when unavoidable’.

Similarly responding to this anxiety over the dangers of spectacle use, the Royal College of Surgeons of England released a pamphlet in 1867, which advised people as to the ‘requirements that should in all cases be possessed by the optician to whom the selection of spectacle lenses is entrusted’. These included:

- An intimate knowledge of the anatomical structure of the eye, and of the theory of vision.

- An extensive acquaintance with the science of optics.

- A sound mathematical knowledge.

- A practical acquaintance with the manufacture of lenses and spectacle frames.

Unlike other doctors of the period, the Royal College of Surgeons were not against the use of spectacles altogether, but rather encouraged people to buy from respected opticians.

Guide Dogs

Guide Dogs

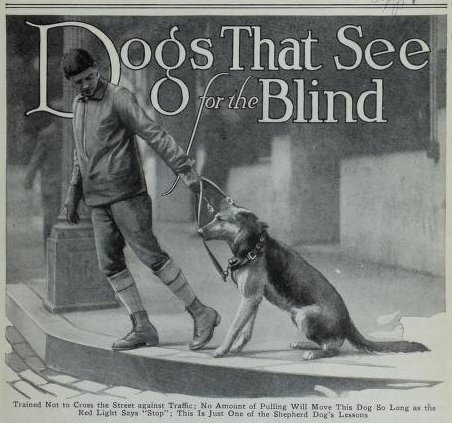

For as long as people and dogs have been living together, dogs have been used by blind people as assistive aids. For example, scholars such as Michael Tucker have argued that an image of a guide dog appears in a first-century AD mural in the ruins of Roman Herculaneum! We also find images of guide dogs in several medieval manuscripts (such as Walters Art Museum, MS 82, fol. 207r.), and later they appear in Victorian literature. Charles Dickens, for example, writes in A Christmas Carol that, ‘even the blind men’s dogs appeared to know him [Scrooge]; and when they saw him coming on, would tug their owners into doorways and up courts’. However, it was not until after the First World War that guide dogs began to be trained and issued en masse.

One of the early pioneers in the training of guide dogs en masse was Dorothy Harrison Eustis. Eustis was working as a dog breeder and trainer in Switzerland when she first heard that a large guide dog training centre had been set up in Potsdam, Germany. Intrigued by their methods, Eustis visited the centre for several months and later wrote in Dogs as Guides for the Blind that, ‘since the Great War, Germany has developed the training and use of these dogs on a very large scale and to-day almost every German war blinded soldier capable of handling a dog has one provided by the Government and receives an allowance for it’s maintenance’.

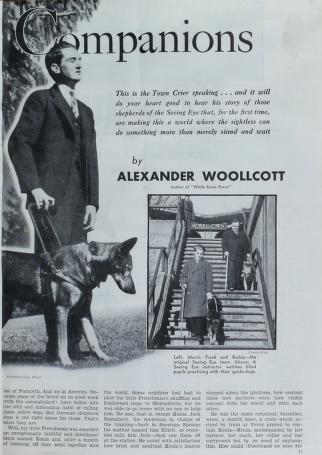

Inspired by this system, Eustis wrote an article about the Potsdam training centre for the Saturday Evening Post in 1928, stressing the independence that guide dogs could bring to people with ocular impairments. Shortly after publication, she received a letter from a young blind man named Morris S. Frank, asking how he might help to set up a similar institution in America. He stated that, ‘I wrote to Mrs. Eustis to find out where I could obtain such a dog she answered that it was true that these shepherds would do these things and that, while they could not be procured in America, she would be glad to have a dog trained for use under American conditions, and train me with the dog’. Frank took Eustice up on her offer and together they worked to train Buddy the Guide Dog. Buddy was so successful that Frank and Eustice subsequently worked together to found ‘The Seeing Eye’ guide dog school.

Training Guide Dogs

Training Guide Dogs

So how then did Eustis and her team at The Seeing Eye train these dogs for their roles as sighted guides? Well, first of all dogs had to be specially bred and raised. German Shepherds were generally considered the best breed of dog to become guides. As Dickson Hartwell points out, German Shepherds were of a good size, easy to keep clean, and intelligent without being unthinkingly obedient. Other dogs, he says, do not possess this same combination of skills. For example, although a ‘French poodle could learn the routine of guiding a blind person in about two-thirds of the time it takes to teach it to a German Shepherd […] [when] faced with an open manhole, the poodle on the command “forward” would not go left or right and around the manhole but it would, as has been demonstrated in tests, attempt to jump it, to the imminent and serious risk of it’s blind charge’.

When these German Shepherd puppies were of an age to begin their training, they were entered into a three month programme. During this time, a sighted trainer will take ‘the student dog through city streets and other given routes until she learns to meet any situation which may be encountered’ (House and Garden, 1934). During this time, the dog would participate in several ‘blindfold tests’, whereby the sighted trainer would be blindfolded and the dog would be expected to guide them through city streets. The harnesses that these dogs wore (both in training and in their lives as guides) were of crucial importance to their work. Unlike a pet or companion dog who may be walked on a fabric lead attached to a collar, guide dogs from The Seeing Eye were ‘equipped with an especially built harness which has a stiff “U”-shaped lead’ (New York Sunday Mirror, 1932). The stiffness of this lead would allow the guidee to be more easily directed by the movements of the dog.

After successfully passing these three months of training, these dogs would be carefully matched with a blind person, with whom they would undergo another round of training. The blind individuals would be taught how to care for their dogs (e.g. how to clean their fur, what to feed them etc.), before being shown how to work with their guide dog as a team. As Morris S. Frank discussed in an interview for Family Circle in 1945, ‘our job here is not only teaching dogs, but teaching men […] when a man learns that to follow his dog he must stand up with his shoulders square (so that the dog’s shoulder will be in line with his knee when he walks beside her), and when he finds that he must walk briskly so that her stops will mean something to him, he seems to take a new lease on life’.

Living with a Guide Dog

Living with a Guide Dog

Within our collections, we have a number of sources that include testimonies from people that received guide dogs from The Seeing Eye. For example, Colonel Fred Fitzpatrick (who, after Morris S. Frank, owned the second guide dog in the United States), said of his dog: ‘I do not know what I would do without Eric. I could not get along without him’. Similarly, Rose Resnik, writing in 1942, says of her guide dog Ilsa: ‘her patience and efficacy as a guide are constant sources of marvel to me. Never is there a hint of irritability or resentment during the long hours under the seat in the theatre or concert […] Day or night she is always ready and glad to go where I need her’.

However, in the early days of guide dogs, not everyone understood the importance of these animals. For example, Hector Chevigny stated that ‘we go to restaurants for lunch or dinner. When I am seated, Wizard [the guide dog] downs obediently at my feet. Occasionally head waiters are outraged at the very thought of a dog’. He goes on to explain that he didn’t waste his time explaining Wizard’s role to these people and instead found restaurants that were happy to have them. Rose Resnick also describes how some people did not trust guide dogs to do their jobs properly and, in their efforts to help, caused more trouble than good. She recalls how, when she and her dog got out of a street car one day, ‘the conductor, against my remonstrances, got out with me and literally shoved me through two cars which were parked near the curb. Ouch – my shin hit the bumper of one of them. This would never have happened if he had let my dog guide me through them’!

Reading Devices

Reading Devices

The final section of this Source Set will consider the development and use of ‘Reading Devices’. As we will see, the reading technologies discussed below could be divided into three categories: those that were specifically designed for individuals with visual impairments and used by said individuals; those that were not designed to function as disability technologies, but were rapidly taken up by individuals with visual impairments; and those that were designed to benefit the visually impaired community, but were taken up just as enthusiastically by individuals without visual impairments. As a result, this final section also serves to demonstrate the ways in which assistive aids influenced the development of technology more broadly (and vice versa).

Braille

Braille

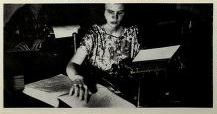

Braille (a system of raised dots that individuals can read with their hands) is arguably the best known reading device for individuals with ocular impairments. It was invented by Louis Braille in 1824 – when Louis was only fifteen years old!

While studying at the School for the Blind in Paris, Braille had been introduced to a method of communication called ‘Night Writing’. This had been developed by a man named Charles Barbier who had served in Napoleon’s army. Barbier had noticed that soldiers would light lamps to read important military correspondence at night. However, the light from these lamps frequently drew the attention of enemy forces, revealing the location of the army, and resulting in casualties. In order to avoid this, Barbier constructed a system of raised dots and dashes that soldiers could read with their fingers, without the need of a light. Braille was inspired by this idea, but thought that Barbier’s system was too complicated, so worked on simplifying and refining the system for use by blind people. In 1854, France adopted Braille as its’ official communication system for blind people.

However, despite the invention of Braille in the nineteenth-century and the early adoption of Braille by the French, it was not used by English speakers until 1932. As such, a lot of the material in our collections that concerns Braille dates from the twentieth century – such as Madeleine Seymour Loomis’s book, You Can Learn to Read Braille. Prior to this, English speakers had been using ‘Moon Type’, designed by William Moon in 1845. This system consisted of simplified versions of letters from the Roman alphabet which were subsequently embossed so as to be read by hand. In her article, The Reconstruction of the Blind in France, Isabel W. Kennedy suggests that, in the case of individuals with hardened fingertips who could not feel the nuances in dotted writing, Moon Type was more valuable than Braille. It was also lauded as being easier to understand by individuals who had lost their sight in later life and already recognised letters from the Roman alphabet. Nevertheless, Moon Type was also a much slower system of reading and the similar shapes of some letters could cause confusion amongst readers. As such, it was generally superseded by Braille in the mid-twentieth century. A good example of this can be seen in a 1958 Manual for Instruction in Braille and Moon Type in which seven pages are devoted to Braille and one sentence is given to Moon Type.

The Electric Eye

The Electric Eye

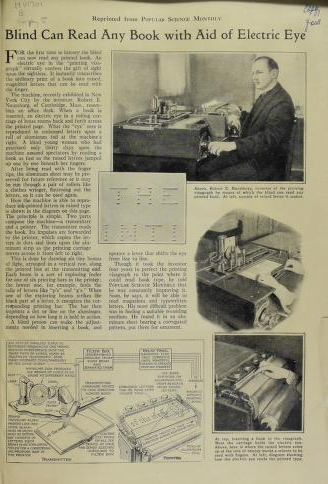

Another device, which shortly predates the use of Braille by English language speakers, is the ‘Electric Eye’ designed by Robert E. Naumberg in 1931. As discussed in the magazine, Popular Science Monthly, this device ‘instantly transcribes the ordinary print of a book into raised magnified letters that can be read with the finger’, and therefore did not require users to learn a new system of reading. This (like Moon Type) was desirable for individuals who lost their sight later in life and subsequently recognised Roman letters. However, this embossed version of the Roman alphabet was not optimised for blind readers. Not only was this process of reading slower, but it was also easier to mistake similar letters for one another. On top of this, the device was large (around the size of an office desk), complex, and would have been expensive to run. It was not a machine that could, practically, be kept in the homes of ‘ordinary’ people. As such, and unfortunately for Naumberg, the Electric Eye remained a largely undesirable piece of equipment

Radio

Radio

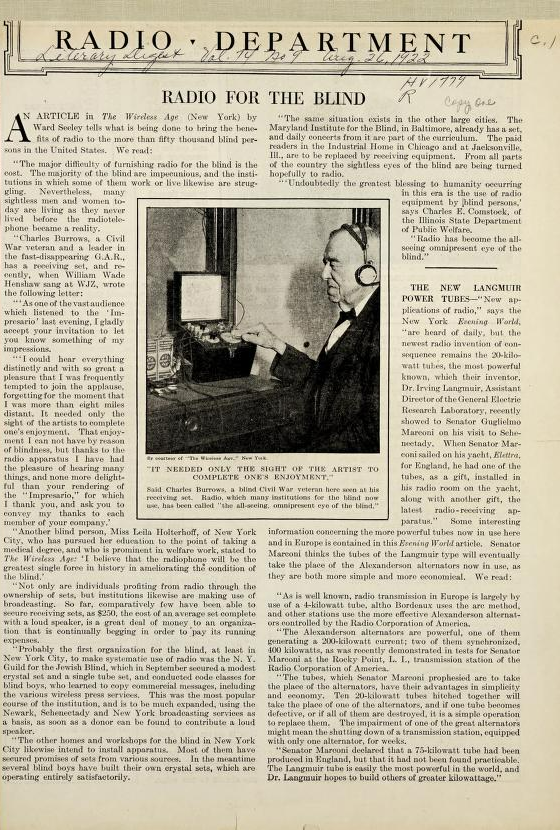

Despite its earlier use as a military technology, radio was increasingly adopted as a civilian commodity throughout the 1920s. Although this system of conveying the news and providing entertainment was not specifically designed with blind people in mind, radio rapidly became an indispensable disability technology for individuals with ocular impairments. For example, in a 1929 Town Crier article, ‘What Radio Means to the Blind’, a Massachusetts woman is cited as saying that, when she listens to the radio, ‘I forget my blindness, forget everything except that I am one of the many thousands enjoying the same great pleasure’. Similarly, in a 1922 Reader’s Digest article titled ‘Radio for the Blind’, a Miss Leila Holterhoff, of New York City, is quoted as saying: ‘‘I believe that the radiophone will be the greatest single force in history in ameliorating the condition of the blind.’

However, radio faced one major challenge in becoming a widely used disability technology – it was very expensive to purchase a radio set. As Ward Seely points out in 1922, an average radio set cost around $250 (approximately $4,115 by today’s standards!) Whilst some blind people tried to avoid these high prices by building their own radio sets (as can be seen in the case of Dr. Marks, who describes how he builds and operates his own short-wave transmitters in a 1932 article ‘Radio for a Dark World’), others set up schemes through which individuals and companies could donate radios to blind individuals. For example, by 1929, the American Foundation for the Blind had ‘distributed 3,500 radios among blind people, through the cooperation and generosity of the public, the press and the foremost radio manufacturers in the United States’.

Talking Books

Talking Books

In 1934, the Literary Digest labelled Talking Books as ‘the most important development in aids for the blind in the last hundred years’. They go on to state that these Talking Books will ‘free braille readers of the laborious task of fumbling through endless pages of embossed letters, and enable blind people who cannot read braille to read novels and non-fiction by ear’. But what were these ‘Talking Books’?

Talking Books were first conceived of by a man named Ian Fraser. Fraser had lost his sight after having been shot at the Battle of the Somme and, despite having learnt Braille, was frustrated with how long it took to read a book in this format. In 1918, he began working with the Royal National Institute of Blind People to find a solution to this problem. To begin with, Fraser tried to record books on gramophone records, but these could only hold up to five minutes of content. By 1934, Fraser and his team had developed records that could play for up to 25 minutes per side. From this, the Talking Book (a ‘ten double-sided 12 inch gramophone disks, each side with a playing time of about 25 minutes’) was created. Shortly after, this idea was taken up by Robert B. Irwin, Executive Director of the American Foundation for the Blind, enabling Talking Books to become an international phenomenon.

However, like radio sets, Talking Books were often too expensive for people to buy. As such, a series of Talking Book Lending Libraries emerged through which people could borrow these items at no cost. In 1937, the Literary Digest reported that twenty-seven libraries across America offered a selection of 200 talking books. These books would then be sent free to the borrower through the mail, and then, like an ordinary library, the borrower would return the book on completion.

Although this technology was initially developed for blind people, ‘talking books’ have proved incredibly popular with sighted people too. In 2021, it was reported that 46% of Americans over the age of eighteen had listened to at least one audiobook!

Bibliography

Please find a list of the sources referenced in this set below.

- Ackland, W., Hints on Spectacles: When Required and How to Select Them (London: Horne & Thornthwaite, 1867)

- Aldous, Donald W., ‘Talking Books’, American Music Lover, 2:4 (1936)

- American Foundation for the Blind, Manuals for Instruction in Braille and Moon Type (New York: American Foundation for the Blind, 1958)

- Anon, ‘Blind Can Read Any Book with Aid of Electric Eye’, Popular Science Monthly, 119:1 (1931)

- Anon, ‘Books Talk: Records Carry Blind “Readers” Through Novels and Poetry Without Braille’, Literary Digest, 123:21 (1937)

- Anon, ‘Dogs that See for the Blind’, Popular Mechanics, 52:1 (1929)

- Anon, ‘Radio for the Blind’, Literary Digest, 74:9 (1922)

- Anon, ‘Science and Invention Begin to Aid the Blind: Lending Libraries of “Talking Books” Which Enable the Sightless to Read by Ear, Are an Important Development’, Literary Digest, 117:18 (1934)

- Anon, ‘Shepherd Dogs as Guides for the Blind’, House and Garden, 65:1 (1934)

- Anon, ‘What Radio Means to the Blind’, Town Crier (June 1929)

- Anon, ‘Why the Blind Nowadays Go to the Dogs to Guide Them in Their Darkness’, New York Sunday Mirror Magazine Section (June 26, 1932)

- Beer, Georg Josef, The Art of Preserving the Sight Unimpaired to an Extreme Old Age, and of Re-establishing and Strengthening it when it Becomes Weak (London: Printed for Henry Colburn, 1815)

- Bond, Frank Fraser, ‘Writ in Sound’, Saturday Review of Literature (January 28, 1939)

- Carter, Robert Brudenell, On Defects of Vision which are Remediable by Optical Appliances (London: MacMillan and Co., 1877)

- Chevigny, Hector, ‘My Eyes Have a Cold Nose’, Reader’s Digest, 45:270 (1944)

- Christensen, W. A., Almo, His Master’s Eyes: A True Story of a Famous Hero Eye Dog (Los Angeles: De Vorss & Co., 1935)

- Curtis, John Harrison, Observations on the Preservation of Sight, and on the Use, Abuse, and Choice of Spectacles (London: Renshaw & Rush, 1834)

- Eustis, Dorothy Harrison, Dogs as Guides for the Blind (Lausanne: Imprimerie Delacoste-Borgeaud, 1929)

- Fox, L. Webster, ‘A History of Spectacles’, Medical and Surgical Reporter (May 3, 1980), 1-7

- Hartwell, Dickson, ‘Training Seeing Eye Dogs’, Science Digest,13:1 (1943)

- Horner, Friedrich, On Spectacles: Their History and Their Uses (London: Ballière, Tindall & Cox, 1887)

- Kennedy, Isabel W., The Reconstruction of the Blind in France (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Home Teaching Society and Free Circulating Library for the Blind, 1917)

- Loomis, Madeleine Seymour, You Can Learn to Read Braille: A Course in Reading Standard English Braille with the Assistance of Any Sighted Reader (New York: The New York Institute for the Education of the Blind, 1939)

- Moon, Robert C., ‘The Moon Type for the Blind’, St Nicholas (May 1910)

- Moschzisker, F. A. von, Spectacles: Why and When to Use Them, or, Near and Far-Sightedness: The Use and Abuse of Glasses (Baltimore: Printed by Hedian & O’Brien, 1856)

- Noyes, Henry Drury, How to Choose Glasses: Being Suggestions to Practical Opticians (New York: William Wood, 1880)

- Oliver, George Henry, An Address on the History of the Invention and Discovery of Spectacles (London: British Medical Association, 1913)

- Percival, Archibald Stanley, The Prescribing of Spectacles (Bristol: John Wright & Sons, 1910)

- Pixley, C. H., The Eye, its Refraction and Accommodation: A Brief Description of the Mechanical Conditions which make Spectacles a Necessity (Freeport, ILL: Home Office, 1889)

- Resnick, Rose, ‘My Adventures with a Seeing Eye Dog’, Our Dogs, 1:3 (1942)

- RoBards, M. J., ‘Touching Sight’, Louisville and Nashville Employees Magazine, 25:7 (1949)

- Roosa, D. B. St. John, Defective Eyesight: The Principles of its Relief by Glasses (New York: The MacMillan Company, 1899)

- Sichel, Jules, Spectacles: Their Uses and Abuses in Long and Short Sightedness; and the Pathological Conditions Resulting from their Irrational Employment (Boston: Phillips, Sampson, 1850)

- Snyder, Mrs William A., ‘Talking Books for the Blind: Mrs. William A. Snyder Describes Invention of Great Service to Sightless: An Article for Inner Mission Month’, The Lutheran, 18:38 (1936)

- Tarkington, Booth, ‘The Seeing Eye Dog’, Ladies Home Journal, 54:9 (1937)

- The Seeing Eye Inc., Here is Freedom! (Morristown: The Seeing Eye Inc., 1934)

- Thorndyke, Harriet, ‘A New Pair of Eyes’, Family Circle, 6:1 (1935)

- Woollcott, Alexander, ‘The Good Companions’, Cosmopolitan Magazine (August 1936)