– by Julia Jablonowski

Most people in our contemporary society are familiar with anorexia nervosa –more commonly known as just “anorexia.” Yet few know the development of medical thought and the advancement of medical etymologies in the Victorian era that led to the emergence of what we know today as anorexia nervosa.

Prior to the pathological conception of anorexia nervosa, its fundamental symptoms, which are grounded in self-inflicted food aversions, were not thought of as an independent disorder until the nineteenth century. A common diagnosis that was used in the days before anorexia nervosa was hysteria, a disease historically exclusive to the female gender.[1]

In the Victoria era, a woman was societally understood to be passive, feeble, emotional, and fragile.[2] These beliefs as espoused by Victorian culture created a space in which women were understood to be societally, and medically, more susceptible to illness. From mood swings to fevers, light-headedness to exhaustion, it seemed that almost any physical or mental affliction residing within the body and psyche of a woman could be met with the diagnosis of hysteria. Other symptoms included a vast array of nervous and erratic behavior projected by women in the form of fatigue, food refusal or self-starvation, depression, bodily pains, anxiety, and the general feeling of unwellness.[3] Because of the broad symptoms of hysteria, it was applied to a large expanse of medical, mental, and emotional cases troubling the fragile Victorian female.

This identification of food refusal and self-starvation developed into an area of independent study in the nineteenth century, largely due to the high mortality rates of mental asylum patients in the United States and the United Kingdom.[4] An English physician, Robley Dunglison, moved to America in 1825 to become a professor of anatomy and medicine. [5] [6] While in the United States, Dunglison was instrumental in the establishment of Pennsylvania’s first state asylum where proper provisions were made to treat the insane poor of Pennsylvania.[7] Coincidentally or not, Dunglison’s position within the development of institutional asylums had a large impact on the evolution of the vocabulary we associate with self-inflicted food refusal.

In 1856, Dunglison published Medical Lexicon: A Dictionary of Medical Science. This medical dictionary defines a premature understanding of the word anorexia, then referred to as “anorex’ia,” which he defined as the “absence of appetite, without loathing.”[8] Dunglison’s dictionary elaborates on this new term, continuing the journey of the disorder’s etymological advancement, mentioning “anorexia exhausto’rum,” which is the “frigidity of the stomach.”

Anorexia began to be noted as an individual disorder rather than a symptom of a larger disease such as hysteria, due to the level of accountability asylums where held to in the public spheres of the U.S. and Britain. Anorexia began to be distinguishable as its own malady because of the level of transparency promoted by medical journals and newspapers that reported on mortality rates in such institutions.[9] In American asylums, the superintendents were held accountable through the spectacle of death by starvation, which was a frightening source of mortality to the public.[10] An asylum’s mortality statistics were published in professional medical journals, as well as abstracted in newspapers for society’s lay people.[11] A high mortality rate communicated immense failure on the part of the asylum. British asylum keepers were becoming increasingly aware of this transparency and the repercussions that followed when people began to catch on to the increasing numbers of premature patient deaths due to self-starvation in an institution meant to care for the ill, thus allowing for the disease to gain special attention. [12]

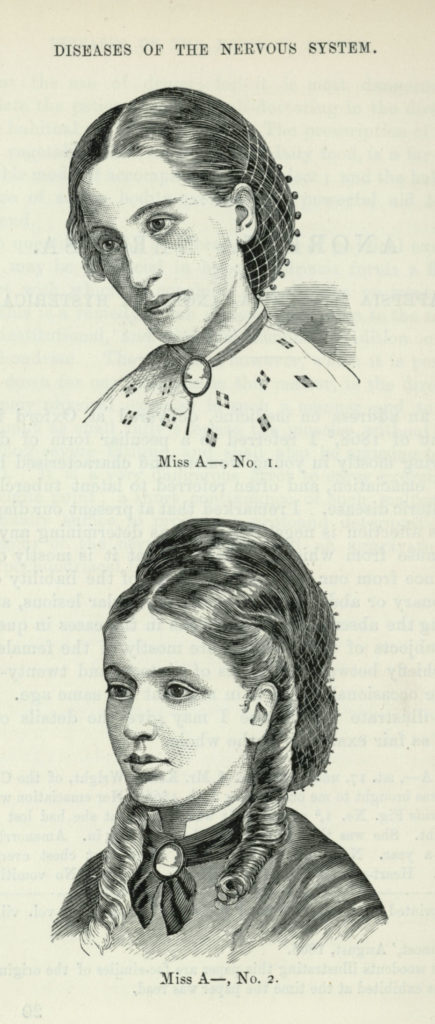

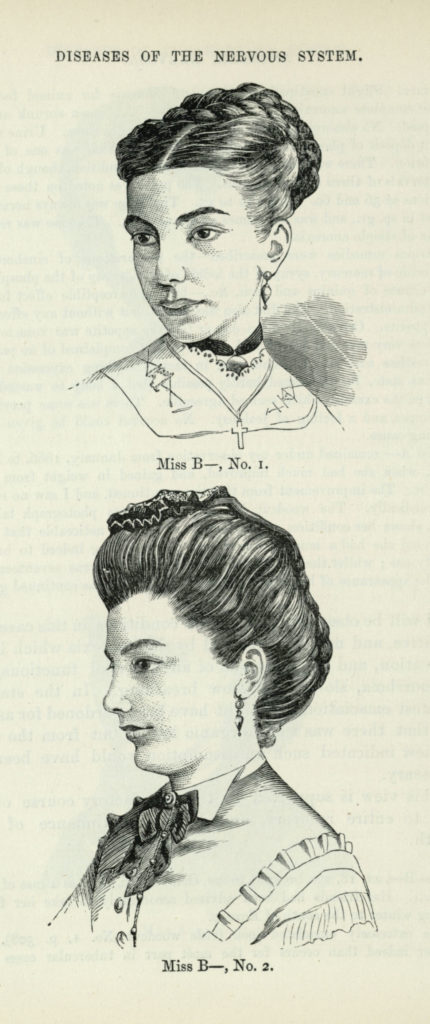

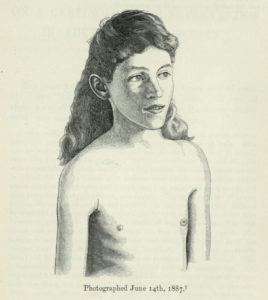

The attention drawn to this disease was largely addressed by two medical professionals: Parisian neuropsychiatrist, Ernest Charles Lasègue, and London physician, Sir William Withey Gull. Lasègue, a contemporary of Gull, was responsible for the term “l’anorexie hysterique” –hysterical anorexia. Gull combated this name and proposed the name anorexia nervosa, which he publicly expressed in August 1868 in his address at Oxford University.[13] The significance of this terminological substitution of “nervosa” for “hysterique” was crucial to Gull because hysteria, as understood by Victorian medicine, was exclusively a woman’s plague. Although anorexia mostly affected the female population, Gull noted that it, too, plagued men, thus leading to the necessary use of the word nervosa, which focuses on anorexia’s association as a nervous, mental, and genderless disease.[14]

When defining the term anorexia nervosa in his address at Oxford, Gull explained:

“The want of appetite is, I believe, due to a morbid mental state. I have not observed in these cases any gastric disorder to which the want of appetite could be referred. (…) We might call the state hysterical without committing ourselves to the etymological value of the word, or maintaining that the subjects of it have the common symptoms of hysteria. I prefer, however, the more general term ‘nervosa,’ since the disease occurs in males as well as females, and is probably rather central than peripheral.”[15]

This gender-inclusive research of Sir William Withey Gull, in addition to the growth of mortality rates –and public embarrassment—being suffered by asylums, shifted the understanding of self-starvation in medicine. This shift thus demanded intellectual and terminological changes to be made, resulting in the emergence of anorexia nervosa.

Notes:

[1] Cecilia Tasca, Mariangela Rapetti,, Mauro Giovanni Carta, and Bianca Fadda, “Women And Hysteria In The History Of Mental Health,” Clinical Practive & Epidemo=iology in Mental Health, 8, (2012): 110-111.

[2] “The Hysterical Female,” Restoring Perspective: Life and Treatment at the London Asylum, https://www.lib.uwo.ca/archives/virtualexhibits/londonasylum/hysteria.html.

[3] “The Hysterical Female,” Restoring Perspective: Life and Treatment at the London Asylum, https://www.lib.uwo.ca/archives/virtualexhibits/londonasylum/hysteria.html.

[4] Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Fasting Girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease.

[5] “Professor and Physician: Robley Dunglison, M. D.; The Dunglisons Reach the University of Virginia,” The University of Virginia, http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/dunglison/at_uva/.

[6] “Professor and Physician: Robley Dunglison, M. D.; From Kewsick, England to Charlottesville, Virginia,” University of Virginia, http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/dunglison/keswick/.

[7] An Appeal to the People of Pennsylvania on the Subject of an Asylum for the Insane Poor of the Commonwealth, (Philadelphia, 1838).

[8] Robley Dunglison, M.D., LL.D., Medical Lexicon: A Dictionary of Medical Science, (Philadelphia, Blanchard and Lea., 1856), 80.

[9] Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Fasting Girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1988), 101.

[10] Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Fasting Girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1988), 101

[11] Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Fasting Girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease.

[12] Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Fasting Girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1988), 101.

[13] Gull, William Withey. “V.-Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica).” Obesity Research 5, no. 5 (September 1997): 498–502

[14] Gull, William Withey. “V.-Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica).” Obesity Research 5, no. 5 (September 1997): 498.

[15] Gull, William Withey. “V.-Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica).” Obesity Research 5, no. 5 (September 1997): 501.

Sources:

An Appeal to the People of Pennsylvania on the Subject of an Asylum for the Insane Poor of the Commonwealth, (Philadelphia, 1838).

Dunglison, Robley M.D., LL.D., Medical Lexicon: A Dictionary of Medical Science, (Philadelphia, Blanchard and Lea., 1856), 80

Gull, William Withey. “V.-Anorexia Nervosa (Apepsia Hysterica, Anorexia Hysterica).” Obesity Research 5, no. 5 (September 1997).

Jacobs Brumberg, Joan, Fasting Girls: The Emergence of Anorexia Nervosa as a Modern Disease, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1988).

“Professor and Physician: Robley Dunglison, M. D.; The Dunglisons Reach the University of Virginia.” The University of Virginia. http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/dunglison/at_uva/.

“Professor and Physician: Robley Dunglison, M. D.; From Kewsick, England to Charlottesville, Virginia.” University of Virginia. http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/dunglison/keswick/.

Tasca, Cecilia, Rapetti, Mariangela, Giovanni Carta Mauro, and Fadda, Bianca “Women and Hysteria In The History Of Mental Health,” Clinical Practive & Epidemo=iology in Mental Health, 8, (2012).

“The Hysterical Female.” Restoring Perspective: Life and Treatment at the London Asylum. https://www.lib.uwo.ca/archives/virtualexhibits/londonasylum/hysteria.html.