~Courtesy Chrissie Perella and Beth Lander, MLS, College Librarian, Historical Medical Library.

What is a recipe? Is it instructions from which one can prepare a meal, a snack, a dessert? Or is it how to mix the best cocktail? Or how to cure acne? Or how to care for a bee sting? What other knowledge does one need to properly take advantage of the advice in a recipe? Recipes found in medical books are no different than ones found in food cookbooks; it’s just that the desired outcome is different than a crowd-pleasing cake.

The Historical Medical Library holds over 20 manuscript recipe (or “receipt”) books, dating from the 17thcentury up through the early 20th century. The majority of our recipe books are medical in nature, but many include food, drink, and household cleaning recipes as well. I’ve even seen recipes for ink in a couple of our 19th century books.

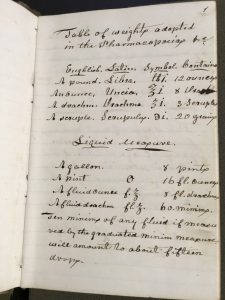

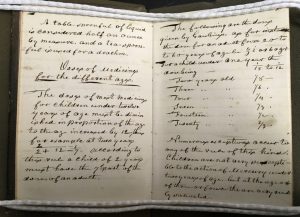

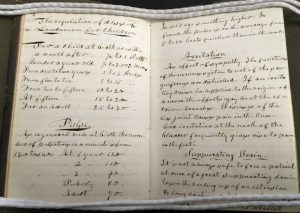

However, the recipe book I’ve chosen to look at for The Recipes Project’s virtual conversation does not contain any ‘extras’ – it is filled with strictly medicinal concoctions. MSS 2/258 (Lancaster County recipe book) is dated to circa 1854 and attributed to an unknown physician from Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. I chose this particular book because I found it interesting that no food, drink, or household cleaning recipes are included. Other unusual features are a table of weights; a conversion table for liquid measures; a summary of “Doses of medicines for the different ages;” a chart of pulse rates, categorized by age; and my favorite, “The regulation of doses of Laudanum for Children.”

“Table of weights adopted by the Pharmacopoeias” and table of “Liquid measure.”

“Doses of medicines for the different ages”

“The regulation of doses of Laudanum for Children” and “Pulse.”

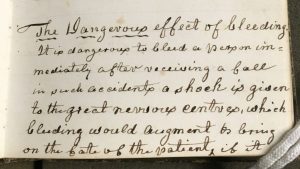

The second section of MSS 2/258 reminds me strongly of student lecture notes. The next 5 pages include explanatory paragraphs about topics such as the circulatory system, irritation or inflammation, and “The Dangerous effect of bleeding.”

It is dangerous to bleed a person immediately after receiving a fall in such accidents a shock is given to the great nervous centres, which bleeding would augment or bring on the fate of the patient, if it be employed before reaction has taken place. D.mm.m.ii.164-5

The Dangerous effect of bleeding.

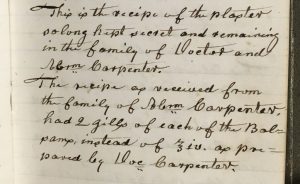

Following the notes are recipes from both botanical and eclectic medical sources, which are often cited. One of my favorite citations is for a recipe for plasters: “This is the recipe of the plaster so long kept secret and remaining in the family of Doctor and Mrs. Carpenter.”

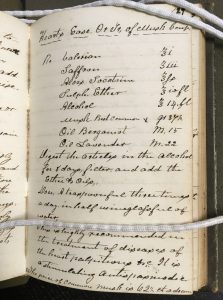

One has to wonder how our physician was able to get the secret plaster recipe from Dr. Carpenter. Another recipe in the book caught my eye because of its name: “Heart’s Ease.” I was curious to see whether this was some sort of tonic or tea, and if it was for what we may term depression/heartache/etc. I found some familiar ingredients (not ALL uses are enumerated here): valerian, used for insomnia as well as depression and conditions related to stress; saffron, for insomnia and depression; bergamot, used in aromatherapy to reduce anxiety; and the all-powerful lavender, useful for insomnia, depression, anxiety, and fatigue. Surprisingly, aloe

s socotrine is listed; it is described in Boericke’s Materia Medica (1901) as

An excellent remedy to aid in re-establishing physiological equilibrium after much dosing, where disease and drug symptoms are much mixed. There is no remedy richer in symptoms of portal congestion and none that has given better clinical results, both for the primary pathological condition and secondary phenomena. Bad effects from sedentary life or habits. Especially suitable to lymphatic and hypochondriacal patients. The rectal symptoms usually determine the choice. Adapted to weary people, the aged, and phlegmatic, old beer-drinkers. Dissatisfied and angry about himself, alternating with lumbago. Heat internally and externally. Has been used successfully in the treatment of consumption by giving the pure juice.

Also listed is “Musk – best common” which is apparently good for stroke, coma, nerve problems, seizures (convulsions), heart pains, and sores.

Well, it was fairly clear to me that either calming and soothing tinctures, teas, and tonics have greatly changed over the past 150 years or so, or I was way off on what this concoction was used for. It turns out that “heart’s ease” is not meant to relieve anxiety, sadness, or anything like that, but for “the treatment of diseases of the heart palpitations.” The tincture is described as a “stimulating antispasmodic.” A stimulating antispasmodic works to prevent or calm spasms by stimulating the higher nervous system.

Recipes like the one above, and recipe books like MSS 2/258, can tell us much about the time in which they were written – what ingredients were familiar and available to the author, what medical or natural philosophy books the author studied or referenced, what ailments were common or considered important to know how to treat, and sometimes even short case studies about the effectiveness of a particular treatment.

What I find most fascinating, perhaps, about many of the Library’s recipe books is that they are non-discriminatory when it comes to choosing recipes: a treatment for kidney stones will be followed by a recipe for roast mutton; something to stop the flux will be followed by hair tonic. But MSS 2/258 is different in that it includes only medical recipes. The nature of the book is more formal and less chatty than some in the collection: I’m thinking specifically of MSS 2/351, (Elizabeth Paschall Coates receipt book), which includes notes like this in recipes:

“Susannah Fowler an old Acquaintance of mine from her Childhood & a person of Good Reputation had a verry bad fellon Coming on her finger. . . this She Says was practised by a woman as a very Grate Secret I Dispersd one for our Girl Rose in 6 or 8 Dressings. . .”

While we know a bit about Elizabeth Paschall Coates, we know nothing about our Lancaster County physician. Where did he attend medical school? Did he have his own practice or did he work in a hospital? The way his recipe book is laid out and the contents it includes suggest that he was a meticulous, thorough person, and therefore was probably a decent doctor. Perhaps he didn’t include food, drink, or household cleaning recipes because he liked everything well organized and in its place – do recipes for bread, punches, or inks belong with medicines?

Even in strictly medical recipe books one will find many answers to the question “What is a recipe?” and perhaps more questions, as well.