Today we are pleased to feature five guest posts from students in Tom Ewing’s Virginia Tech Introduction to Data in Social Context class! This post is from Jack Fleisher, Jae Ha, Joey Hammel.

We chose to explore tuberculosis in California because of a few interesting characteristics. One of these characteristics was the phenomenon of California being seen as a beacon of health and longevity in the late 1800s, and as a result, attracting many individuals sick with tuberculosis thinking that moving there was their best hope to recover and alleviate their disease. We suspected that this would drive up the tuberculosis rates as the increase in the population of those previously diagnosed would raise the death rate above where it would be for the Californian-born population.

California became a destination in the late nineteenth century for tuberculosis patients seeking a climate cure for their incurable disease. This influx of patients, in combination with the wave of immigrants from other states to the Pacific coast of the United States, produced an uneven pattern of tuberculosis deaths across the entire state. Medical records for California illustrate the distinctive patterns as well as the efforts of health authorities to defend their state’s health record from the perceptions prompted by these unusually high death rates.

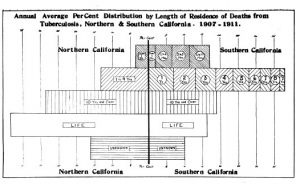

According to the 22nd Biennial Report of the State Board of Health of the State of California “Tuberculosis…is the leading single cause of death in this state, causing over one seventh of all deaths.” TB killed more than all circulatory diseases combined and was nearly four times deadlier than cancer. Illustration A from this report offers a revealing visualization of this relationship between TB and other diseases. The state is divided into halves, with separate data for Northern California and Southern California. While the dividing line between north and south is unspecified, we suspect the area from San Francisco to the Oregon border was Northern California and the area from San Jose to the Mexican border was Southern California. The chart covers a five year period, from 1907 to 1911, and records the average annual percent distribution of tuberculosis deaths by the length of time the victims had resided in California. The chart shows that higher percentages of victims from Southern California had been resident for shorter periods of time, including less than one year and one to nine years. Victims of tuberculosis in Northern California, by contrast, on average had lived longer in the state, including those who had been resident for ten years or more as well as those who were lifetime residents. This chart is meant to illustrate how the influx of tuberculosis patients into Southern California, and particularly in Los Angeles, contributed to the high number of deaths from tuberculosis across the state.

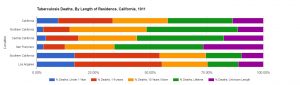

The same data can be visualized using more modern tools as shown in Illustration B, which compares data from Northern, Central, and Southern California with more detailed information for two cities, Los Angeles and San Francisco. In this chart, the percentage of deaths are color coded by length of residency in California. Southern California has higher death rates from residents who have lived there for under 1 year and it seems that fewer long term residents are dying from Tuberculosis. We can then infer that Los Angeles has significantly higher percentages of tuberculosis deaths among new arrivals, victims who have lived in the state for 3 years or less – at a rate of more than 50% of all tuberculosis deaths in that area, whereas the rates for the whole state and especially for Northern and Central California are much lower for new arrivals. Looking at the data you can see that the death rates from TB for lifetime residents for Northern and Central California is significantly greater than those of Southern California. We can also see that San Francisco has a noticeably large proportion of unknown residents (unclear residency status) who are likely to be out of state people seeking for medical help but dying before they can successfully do so. It’s possible, therefore, that some percentage of those listed as “unknown” for San Francisco could in fact result from the city being a transit point for new arrivals — including tuberculosis sufferers seeking a cure in the Golden State. It is possible, therefore, that a higher proportion of people who migrated to San Francisco to look for a cure either established residency but died within the first year or died before they could establish residency.

The above graph shows the change in percentage of total deaths by TB in a few major Californian cities over time. The greatest change happens in Sacramento, which is likely due to a small sample size. The “Sum” section is the average of the other rates, taking the population into account. The rates in Los Angeles are consistently high, due to the previously mentioned phenomenon of sick people travelling there with the promise of better health. There was not much of an overall trend in these cities’ average death rates, as TB was a huge problem for the entire area for the duration of our time period. Each individual city went up or down according to its own unique circumstances or seemingly random or unconnected trends that showed up at the time.

While we found no clear correlation or trend of tuberculosis death rates in each city, analyzing cities can tell a researcher a lot about the larger picture in their data. Not only does it say more about that city, it could identify geographical trends or municipal policy that explain the data. Also, if one of the cities was an outlier, it begs the question of why its data is so far outside the norm for other cities. If larger, poorer, or denser cities exhibit some similar characteristics in their data, a correlation could be drawn. In our data, however, not much separates each of the cities, and the slight differentiation in the data is likely due to random change or a minor measurement error. In reality, tuberculosis was a major problem in all of these cities at this time period. There could be a more interesting trend if we had a longer time frame to analyze over. We expect that tuberculosis death rates would decrease almost uniformly in all cities we looked at over time. Despite no obvious correlation, tuberculosis was a problem in all urban areas in California at the time. In future research, looking at tuberculosis rates in rural regions of the state, if that data is available, would be beneficial to determine if tuberculosis was made worse by urban environments and high population density..

We conclude that the high rates of tuberculosis deaths in San Francisco were mainly due to immigration from states east of California, while the high rates of tuberculosis deaths in Los Angeles were mainly due to journals like The Land of Sunshine, promising healing powers of the California Sun to sick tuberculosis patients. Tuberculosis was a devastating disease in America at the turn of the 20th century that had no known cure. The fact that this feared disease was so devastating in California was due to an unlucky combination of ironically positive factors, such as having economic success and being known for healthiness. This makes California a very interesting area to study in how it relates to tuberculosis during that era. This assignment not only increased our understanding of American history and how to be a better researcher, it also taught us the value and power of data and how it lets us make inferences about how things came to be and how vast its impacts were on people. The story of tuberculosis in California is long and complex, but analyzing data helps tell that story in new ways.

References

22nd Biennial Report of the State Board of Health of California. California State Board of Health, n.d. Web. 22 Feb. 2017. Available from Medical Heritage Library / Internet Archive.