Today we are pleased to feature five guest posts from students in Tom Ewing’s Virginia Tech Introduction to Data in Social Context class! This post is from Brian Yuhas, Claire Ko, Emma Rhodes.

The discussion of socioeconomic factors and their impact on tuberculosis came about as a result of our inadequate knowledge of the disease and our wish to delve deeper into how this disease influenced everyday life in the 1890s. Our research focused on whether economic status had an apparent effect on the deaths that occurred in Boston due to tuberculosis in the late nineteenth century. Did similar population densities have the same tuberculosis rates among different classes? Did wards with higher tax revenue experience higher or lower tuberculosis death rates? Through the 1890s Vital Statistics report for Boston, we were able to come to some conclusions about the correlation between wealth and likelihood of death due to tuberculosis in the city.

During our research, we predicted that the quality of living would correlate with the contagiousness of the disease. For example, in the census, there was a description of ward 11 that indicated it was a wealthier ward. This ward was “filled with clean gravel and had wide streets…occupied mainly by wealthy people in fine dwellings of brick and stone” (p. 72). The consumption death rate was 190.84 in Ward 11 and “during the 6-year period the death rate in this ward was much below the city average,” (p. 72). On the other hand, Ward 13’s description indicated it was a poorer ward because “the buildings were principally frame, many being tenements” (p. 74). Ward 13’s consumption death rate was 587.56, which is quite a bit higher than Ward 11’s consumption death rate. The “death rate in [Ward 13] was higher than in any other ward in the city except ward 8.”

Immigrants were also a factor that had to be considered and we found that “poorer” wards had more Irish and German working immigrants, which could have increased the number of consumption victims. A strong example is also seen in Ward 17’s description: “It was principally a residence section, with brick houses occupied by a good class of residents. The streets were wide and the sewers in good condition. It contained but few tenement houses” (p. 77). In Ward 8, the consumption death rates were the highest out of all of the wards in Boston, 1890. They were at 671.56, “the death rate in this ward [being] higher than in any other ward in the city” (p. 69). However, Boston’s vital statistics provided very little information about this ward, other than that it was “an old part of the city.” Therefore, we could not draw conclusions about the economic condition of this ward.

Sewer quality was brought up frequently in the ward descriptions. We predicted, therefore, that sewer quality affected the susceptibility of poorer wards to tuberculosis. Poor sewers could lead to low sanitation and bad quality of life, thus causing more tuberculosis infections. We also suspected that poorer wards might have lower quality sewers. However, after looking into the data tables and reading the ward descriptions provided by the census for each ward, we concluded that the sewers seemingly had no correlation with consumption. In addition, there was little correlation between the wealth of a ward the quality of its sewers.

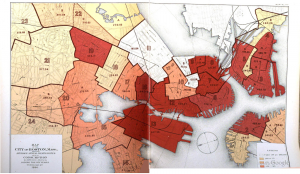

The census gave us a lot of good, observational data that helped us deduce what wards in Boston were considered “wealthy” and “poor.” The census also included a map of Boston, color-coded according to the number/density of consumption deaths in the year 1890. The map provided us with a good overview of the effect tuberculosis had on Boston as a whole in a simplified format. Although this was helpful, there were some limitations to coming to a clear conclusion that one particular ward was wealthy/poor because of the variation in language throughout the ward descriptions. In addition, the map showed only 24 wards, whereas other maps indicated as many as 25 wards. The map was also oriented incorrectly; it faced east more than it did north. Some wards had little to no description while others had a wealth of information, but it was difficult to decide on the economic status of each ward. The census’ observations were also subjective rather than factual, which posed the problem of credibility.

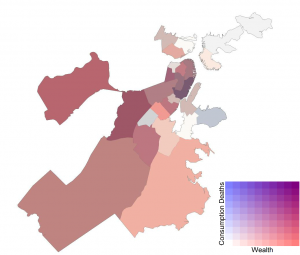

In order to demonstrate tuberculosis’ effect on wealthy versus poor ward, we created a heat map comparing deaths due to consumption and the calculated wealth of a ward. The districts which leaned purple, therefore, would be the ones with both high wealth and high consumption deaths. We expected to see very few, if any, purple wards. However, there were a couple, which at the very least could mean that the correlation between wealth and consumption death was weak. While the map provides important insight, the method used to calculate a ward’s value would have been immensely more accurate if income had been widely reported in the 1890s.

In order to demonstrate tuberculosis’ effect on wealthy versus poor ward, we created a heat map comparing deaths due to consumption and the calculated wealth of a ward. The districts which leaned purple, therefore, would be the ones with both high wealth and high consumption deaths. We expected to see very few, if any, purple wards. However, there were a couple, which at the very least could mean that the correlation between wealth and consumption death was weak. While the map provides important insight, the method used to calculate a ward’s value would have been immensely more accurate if income had been widely reported in the 1890s.

The following table provides the data used in the latter map’s calculations.

| Ward | Consumption Death Rate (per 100,000) | Residents | Total Pop | value/pop |

| 1A | 288.89 | middle | 19633 | 520 |

| 2 | 468.67 | poor | 17297 | 592 |

| 3 | 499.78 | poor | 13094 | 541 |

| 4 | 495.79 | poor | 12842 | 656 |

| 5 | 426.55 | 12412 | 1177 | |

| 6 | 476.72 | poor | 18447 | 3242 |

| 7 | 506.57 | poor | 13145 | 2885 |

| 8 | 671.56 | 13026 | 651 | |

| 9A | 556.48 | middle | 12660 | 2264 |

| 10 | 365.82 | 8205 | 1808 | |

| 11 | 190.84 | rich | 21660 | 5904 |

| 12 | 537.27 | poor | 12585 | 5910 |

| 13 | 587.56 | poor | 22375 | 704 |

| 14 | 372.87 | middle | 26367 | 5456 |

| 15 | 406.86 | poor | 18049 | 4274 |

| 16 | 447.4 | poor | 18048 | 862 |

| 17 | 360.18 | rich | 15638 | 1219 |

| 18 | 239.42 | 16035 | 1585 | |

| 19 | 426.17 | middle | 23016 | 591 |

| 20 | 373.43 | poor | 24335 | 738 |

| 21 | 217.56 | rich | 22930 | 1395 |

| 22 | 230.02 | rich | 20011 | 1636 |

| 23 | 256.89 | 24997 | 1170 | |

| 24 | 256.37 | middle | 29638 | 1075 |

| 25 | 264.26 | 12032 | 1284 |

Vital Statistics of Boston and Philadelphia, covering a period of six years ending May 31,1890 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1895). Available from Medical Heritage Library, https://archive.org/details/vitalstatistics00shungoog