We’re pleased to offer the third part of Dr. Shrady Says by Tom Ewing, Sinclair Ewing-Nelson, and Veronica Kimmerly. You can read Part One and Part Two on the blog and learn more about the Russian Flu project on the project website.

Close reading allows for insightful interpretation of the content, purpose, and structure of texts on a small scale; visualization tools allow for general interpretations of content on a large scale. Neither approach, however, indicates how

7: Mapping Newspaper Reports, January 3, 1890

readers responded to the content of a text or its potential impact on society more generally. In the case of Shrady’s editorial, however, examining the many newspapers across the United States that reprinted claims made in the Medical Record allows for analysis of how this editorial shaped the flow of information during a disease outbreak. On a single day, January 3, 1890, more than twenty newspapers across the United States published, either in full or in an abridged manner, the Medical Record editorial (Illustration 7).

By reprinting this text, these newspapers affirmed that the disease was significant and that the recommendations of this New York doctor and his journal were authoritative. The simultaneous publication of this editorial on a national scale also confirmed the potential for Dr. Shrady to shape the ways that the public understood this epidemic and how the general public could anticipate its future course.

Locating these articles takes advantage of search tools with important applications for both historical analysis and contemporary understanding of disease. A keyword search for disease terms in a newspaper database enables students to construct a timeline based on information dissemination. A search for two terms, “influenza” and “grippe” in Chronicling America (available to the public from the Library of Congress), yields more than 4000 pages for the two months when the epidemic was most widespread, December 1889 and

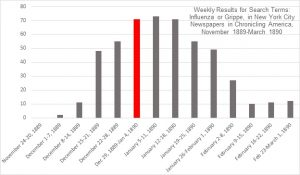

8: Search Results, Chronicling America newspaper collection

January 1890. Reconfiguring searches allows for different perspectives on the timing of the disease. Search results for two newspapers published in New York City indicates how dramatically the coverage increased in December 1889 and especially January 1890, before diminishing in the months that followed (Illustration 8).

Searching using a data range and key words are powerful analytical tools because they make it possible to focus on a set of key issues, locate them geographically, and find important texts, using the highlighted terms on the newspaper pages (illustration 9). Similar searches in other databases, including America’s Historical Newspapers and Proquest Historical Newspapers, available by subscription, produces additional results.

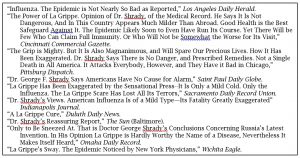

In most cases, these reports simply reprinted the text of Shrady’s editorial, either in full or in an abridged version, with brief introductions that identified the journal as the source. Yet the headlines that framed the articles provided clear indications of the potential significance of the editorial (Illustration 10). The tone of the headlines ranges from reassuring to serious to humorous, thus illustrating the actual scope of reactions to the epidemic that Shrady wanted to shape to fit his own optimistic prognosis.

9: Highlighted Search Terms, Chronicling America, Newspaper Reports on Influenza, January 1890

Editorials published by several newspapers that specifically referenced Shrady’s editorial provide a means to assess the potential impact of this publication. The New York Times, which had initially buried Shrady’s article in a lengthy account of deaths, published an editorial on the following day that offered a more reassuring message to the reading public. Declaring that Shrady’s article would “put laymen in possession of all the professional knowledge about the ‘grippe’ that they can assimilate,” the newspaper endorsed the view that the disease was unusual only in its “extent,” with so many sufferers, but “the danger is very small.” Repeating Shrady’s points about the importance of maintaining good health, the editorial offered this sweeping prognosis of the disease’s likely course: “The duration of the disability depends on the vigor of the patient and the skill with which he is treated. It is plain, therefore, that a cold that might ordinarily be neglected without much risk now requires professional advice. The omission to take such advice may involve confinement for a week instead of a day or two.”

On January 4, 1890, the Harford Courant declared that readers anxious about the influenza must have found the Medical Record article “not only interesting but (to a certain extent) comforting reading” for these reasons: “It is comfortable to be assured on such high professional authority that the disease on this side of the Atlantic is of a very mild type, that the reports from the other side have grossly exaggerated the mortality there, that no American citizen has yet succumbed to ‘grip’ pure and simple, so far as known, and that the danger of resultant pneumonia or bronchitis is by no means so great as it has been popularly supposed to be.” The editorial endorses Shrady’s recommendations to avoid fatigue and eat regular meals, and then elaborated on the potential impact on public attitudes and perceptions: “The Medical Record might well have extended its prescription by adding, Don’t worry! The imagination is always likely to be abnormally active in these cases, and is responsible for a great deal of mischief that is wrongfully laid to the atmospheric conditions, the microbes, etc. As sensible, rational care of one’s self is never labor wasted, grip or no grip, so nothing was ever yet gained by fretting, and fancying symptoms, and borrowing trouble. That is a sure way of making bad enough a great deal worse.” This newspaper editorial thus extended and amplified the potential impact of Shrady’s editorial by endorsing his view that the grippe was not a cause for concern and, if anything, the danger of excessive “fretting” was worse than the disease itself.

10: Newspaper Headlines, January 3, 1890, about Shrady’s editorial

The Los Angeles Times introduced its editorial commentary on January 4, 1890 by anticipating that “some of the more nervous residents of the Pacific Coast are inclined to become a little alarmed at the steady march of the epidemic from the East,” yet the editorial quickly reassured readers: “There appears to be no ground for such alarm.” Highlighting statements from Shrady about the mild nature of the disease, the editorial quoted the entire section claiming that death reports had been exaggerated and not a single fatality in the United States could be attributed to “a pure and simple attack of the disease.” After referring to earlier outbreaks of influenza in American history, all of which had turned out to be quite mild, the Los Angeles Times returned to its regional perspective to provide further reassurances: “It may be added that the health-giving atmosphere of Southern California should secure us from more than a very mild visitation of this sickness, although the unusual moisture now prevailing will be more favorable to its spread than would our usual weather.” The Los Angeles Times editorial writers, like those in New York and Hartford cited above, thus invoked the expert advice presented by Dr. Shrady to persuade readers that the Russian influenza was not severe, that few deaths would result, and that worrying about the disease was potentially more dangerous than its actual medical impact.

Although American newspapers continued to report extensively about the Russian influenza for the next several weeks, particularly as death rates spiked across the United States, increasingly fewer articles referenced the editorial intervention by the Medical Record. The journal continued to report on the course of the disease, but it did not reprint another editorial for two weeks, until January 25, 1890, and this statement did not attract nearly the same attention as had editorials published early in the epidemic.

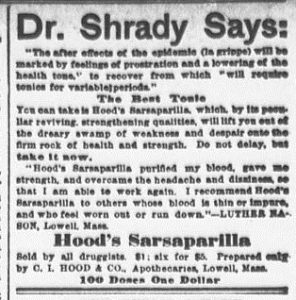

11: Advertisement, The Sun (New York City), January 12, 1890

Yet Shrady’s name, and more importantly, his authoritative pronouncements, remained part of the discourse of influenza in the form of widely distributed, and frequently repeated, advertisements for Hood’s Sarsaparilla, which quoted the Medical Record editorial about the “after effects of the epidemic (la grippe)” and then recommended the “peculiar reviving strengthening qualities” of this tonic sold by druggists. The bold headline in the advertisement, “Dr. Shrady Says” illustrates the powerful influence of a medical expert in a context of public anxiety about the effects of a widespread epidemic (Illustration 11). This advertisement appeared as early as January 12, in The Sun, just over a week after the editorial was published. The same advertisement, all under the headline, “Dr. Shrady Says,” also appeared in other newspapers from New York City, Washington, Pittsburgh, St. Paul, and doubtless many more cities. The use of a medical expert to authenticate the health claims of a commercial product was common in this era when government agencies did not have any regulatory power over health products. In this context, the use of Dr. Shrady’s name in such a prominent way confirms that his influence as a medical expert had potentially broad effects on public perceptions of disease during a time of medical crisis.

This research on the Medical Record in 1889-1890 provides a method for understanding contemporary and future disease outbreaks, especially in situations where diseases are first noticed in other parts of the world, where medical experts are uncertain about the scope and severity of the disease, and where the public expresses a high level of anxiety, stoked in part by alarmist media reports. In these situations, medical authorities such as the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the National Institutes of Health seek to provide the public with clear and detailed explanations of the disease, updated and accurate numbers of victims, and effective methods for prevention, containment, and treatment. Most importantly, medical authorities must balance the obligation to warn the public of serious health dangers with the dangers of exaggerating fears and provoking alarm. Shrady’s editorial about the Russian influenza successfully identified the trajectory, symptoms, and likely course of this disease as it reached the United States. As shown in the newspaper reports published on the same day of the editorial, and confirmed by subsequent reports of an increasing number of deaths due to influenza, his prediction that the disease would not prove a serious threat to public health underestimated the severity and scope of the epidemic. A careful reading of the text of this editorial combined with a broad assessment of its national impact illustrates the potentially significant role that medical authorities can exercise in the earliest and most challenging stages of a disease outbreak.