~Rachael Gillibrand, MHL Jaipreet Virdi Fellow for Disability Studies, 2021

When people discuss hearing aids today, it is likely that they are referring to the small electronic devices that sit either behind the ear or inside the opening of the ear. At the most basic level, these hearing aids work by receiving sound through a microphone, converting this sound into a digital signal, amplifying this digital signal, and then playing the amplified sound into the ear through a speaker. However, recent technological advances have allowed for artificial intelligence systems to be used in hearing technology to balance soundscapes to suit an individual’s unique kind of hearing loss. Today’s hearing aids are also frequently compatible with specialised apps. In 2020, Apple patented a ‘a portable audio device suitable for use by a user wearing a hearing aid, comprising: a proximity sensor to detect a measure of distance of the device to an external object’. In plain language, this means that, when receiving a phone call or engaging with audio content, the phone or tablet will use a sensor to discover if the phone user is wearing a hearing aid. If they are, the phone will automatically adjust to the hearing aid (rather than the hearing aid having to adjust to the phone).

However, whilst these new advances in hearing technologies are fascinating, many people had to live with hearing impairments in a time before iPhones, apps, and AI. This primary source set will track some of the earlier developments in hearing technologies – from the hearing trumpet, to the electric hearing aid.

Hearing Trumpet

Hearing Trumpet

The hearing, or ear, trumpet was one of the earliest devices designed for individuals with hearing impairments. As you can see from the image below, hearing trumpets were funnel (or trumpet) shaped devices that helped to increase the volume of close-ranged noises for the user. Acting as an extension of the outer ear, hearing trumpets worked by capturing sound from a desired direction, whilst blocking out unwanted background noises. The earliest known written account of a hearing trumpet can be found in Jean Leurechon’s Recreations Mathématiques (1624), which discusses the use of funnel shaped objects for the amplification of sound. Three years later, Francis Bacon refers to a similar kind of device in his Sylva Sylvarum (p. 347), stating that: ‘Let it be tried, for the help of hearing, […] to make an instrument like a tunnel; the narrow part whereof may be the bigness of the hole of the ear; and the broader end much larger, like a bell at the skirts; and the length half a foot or more’.

In 1669, Giambattista della Porta (also known as Giovanni Battista Della Porta or John Baptista Porta) discussed the construction of wooden ‘instruments’ ‘to put into your ear, as spectacles are fitted to the eyes’. To ‘find the form’ of this device, Porta assesses a range of animals which he considers to have the best hearing. He concludes that, as hares and oxes are very good at hearing and have large and open ears, his hearing aid should also ‘be large, hollow, and open’. However, not everyone was comfortable using a large hearing device for fear that it might draw attention to their disability.

These concerns over the size of hearing trumpets continued well into the nineteenth century. For example, in his Treatise on the Physiology and Pathology of the Ear (1836), John Harrison Curtis complained that many people were dissatisfied with the size of ear trumpets, and demanded more discreet hearing aids instead. This, he argued, was impossible, stating that ‘that the longer the trumpet, the greater will be its power’. To overcome the social discomfort associated with using hearing trumpets, these devices began to be constructed in a range of styles and materials (including silver, horn, shell, wood, and lace) – transforming ear trumpets into desirable and eccentric accessories, rather than unwieldy hearing aids. By the 1950s, Evelyn Waugh confessed to using a hearing trumpet, not because ‘I hear any better for them, but [because] I look more dignified’.

Acoustic Fan

Acoustic Fan

Second on our list, we have the acoustic fan. To a large extent, the acoustic fan was developed in response to people’s discomfort with the conspicuous nature of the hearing trumpet and other contemporary aids. Designed to look like a folding hand fan, the acoustic fan was very popular with higher status women who wished to disguise their use of a hearing aid. Baronne Staff’s My Lady’s Dressing Room (1892) speaks to this, suggesting that ladies who are ‘afflicted with a nervous form of deafness’ ought to use the ‘more graceful appliance’ of an acoustic fan. She states that: ‘When they wish to listen they have but to take the fan, open it, apply the rim to the upper jaw (on the side of the defective ear) and bend sufficiently to give some tension to the bamboo sticks. They will be quite surprised to find that they can hear as well as though they used an audiphone or dentaphone’.

Although the acoustic fan was a ‘new’ technology in the nineteenth century, the methods by which it worked were based on the oldest and most simple hearing aid – cupping one’s hand around the ear. Directing soundwaves into the ear by cupping one’s hands around the outer-ear can result in an acoustic gain from around 7 to 17 decibels (see: Rosalie M. Uchanski, Cathay Sarli, ‘The ‘Cupped Hand’: Legacy of the First Hearing Aid’, The Hearing Journal, 72:4 (2019)). The acoustic fan worked in a very similar way by extending the remit of the outer-ear and improving directionality. However, not everyone was supportive of the use of the acoustic fan. Vincenzo Cozzolino wrote in his Hygiene of the Ear (1892) that the use of an acoustic fan was harmful ‘because by their presence they irritate and contract the external auditory meatus’ – thereby worsening one’s condition rather than improving it.

Dentaphone and Audiphone

Dentaphone and Audiphone

Despite being produced by different companies, the Dentaphone and Audiphone both operated on the same principle of ‘bone conduction’. Ordinarily, sound waves make their way into the ear canal before they are converted into vibrations by the ear-drum. The vibration of the ear-drum moves three tiny bones (known collectively as the ossicles), which then transfer the vibrations into the inner ear. The inner ear (or cochlea) is filled with liquid, which moves in a wave-like motion as a result of these vibrations. This liquid then stimulates tiny hair cells which send nerve impulses to the brain, where they are converted into sound. Bone conduction works by transmitting sound waves directly to the cochlea through the skull – bypassing the ear canal, ear drum, and ossicles. Although a series of individuals had previously drawn attention to the transmission of sound through various materials (such as Aristotle who suggested that ‘everything that makes a sound does so by the impact of something against something else’ – see De Anima, Book 2, Chapter 8, 420 b 15), it was not until the early seventeenth century that this was applied in the diagnosis of hearing impairments. In 1603, Hieronymus Capivacci, a physician who lived and worked in Padua, constructed an experiment to decipher whether an individual’s hearing loss was caused by damage to the tympatic membrane or a lesion of the auditory nerve (Opera omnia cura Johannis Hartmanni Beyeri [Frankfurt: Paltheniena, 1603], Chapter 1: De laeso auditu, p. 589). As Mudry and Tjellström write: Capivacci ‘connected the teeth of a patient to the strings of a sitar by means of a two foot long iron rod. If the patient was able to hear sound from the sitar, a disease of the tympatic membrane was diagnosed, if [they] did not hear anything it was a lesion of the auditory nerve’ (Albert Mudry, Anders Tjellström, ‘Historical Background of Bone Conduction Hearing Devices and Bone Conduction Hearing Aids’, in Implantable Bone Conduction Hearing Aids, ed. by M. Kompis, M.-D. Caversaccio [Basel: Karger, 2011], pp. 1-9 [p. 2]).

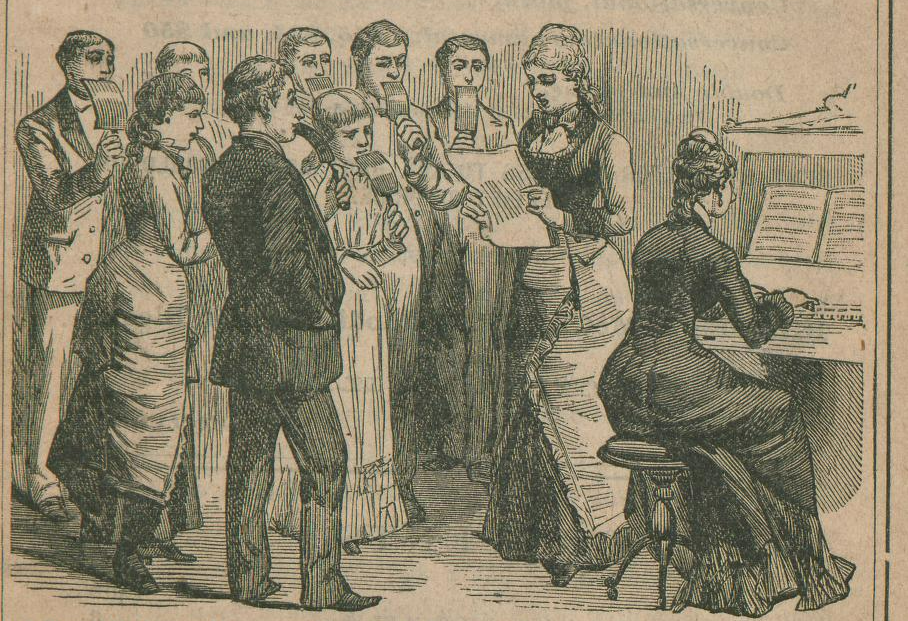

Audiphone

Patented in 1879 by Richard Rhodes, of the Rhodes and McClure Publishing Company, the audiphone was made of a fan-shaped sheet of hard rubber attached to a handle. It worked by using a silken cord to bend the audiphone into a ‘diaphragm’ shape, before inserting the fan into the mouth and holding it against the upper teeth. This allowed for the sound waves to be transmitted through the fan, into the upper jaw bone, through to the inner ear. The tension of the cord could be adjusted depending on the requirements of the user and the nature of sound being heard (voices, music, distant sounds, etc.). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the audiphone’s 1880 advertising brochure, offers a range of customer testimonials expounding the benefits of this technology. For example, E. F. Test states that their audiphone ‘has created quite a sensation among my friends. It was comical to see a number of them fanning themselves with it, under the impression that it was simply a fan, and then in a few moments to see their astonishment when they saw me hearing with it just as well as I ever did’. Similarly, Henry Milnes claimed that, after having been ‘very deaf’ for twenty years, ‘I procured an Audiphone yesterday and can already hear quite well an ordinary conversation, and expect by a little practice to be able to hear sermons, music, etc., without much difficulty’. (Further testimonials of this nature appear in a later, 1882, advertising brochure).

However, not all agreed. In 1881, Laurence Turnbull published Imperfect Hearing and the Hygiene of the Ear. In chapter eight of his book, Turnbull compares the audiphone to other contemporary hearing technologies, such as the hearing trumpet. In his work, he too has a number of personal testimonies which are altogether more negative than those promoted by Rhodes & McClure. For example, one gentleman referred to as I. H. found that, when using the audiphone, ‘he cannot hear, unless the voice of the speaker is so elevated that all his private matters are made known to all around; he also object[ed] to the shape, as being too conspicuous, even in the form of a fan’. Mrs. L, a ‘lady of great refinement’, also tried the audiphone, but claimed that she ‘would not be seen […] with the thing in her mouth all the time. For church and lecture, or opera, she prefers a small pocket ear-trumpet of metal, covered with black velvet’.

Dentaphone

Despite being marketed as ‘a new scientific invention which enables the Deaf to hear by the sound-vibrations conveyed through the medium of the teeth’, the dentaphone was patented a year later than the audiphone and operated on identical principles. Like the audiphone, the dentaphone was a hard rubber fan which could be inserted between the teeth to facilitate the transference of sound waves via bone conduction. Interestingly, in their 1879 advertising brochure, the American Dentaphone Company takes the time to assure potential customers that the dentaphone can be used by wearers of artificial teeth. Although the Audiphone’s brochure mentions this very briefly, the Dentaphone Co. is more thorough, explaining that ‘with this process [of sound transmission] the nerves of the teeth have nothing whatever to do, the vibrations being transmitted entirely through the bony framework of the face and head; and hence, so long as artificial teeth are properly in their place, they conduct the sounds just as well as would the natural teeth’. (For more on dentures as a disability technology, see Set 3: Dentures).

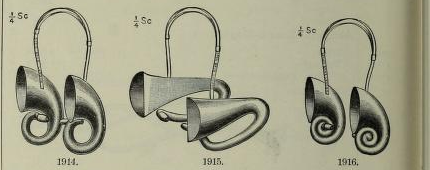

Aurolese Phone

Aurolese Phone

Aurolese phones were first designed and marketed by Frederick Charles Rein (a German manufacturer based in London) in the early nineteenth-century. However they were later manufactured by multiple other companies (such as Down Bros Ltd. and the William V. Willis Company of Philadelphia) under a variety of names, including auricles and cornets. As you can see from the image below, these hearing aids took the form of a headband with a funnel on each side that could be inserted into the ear. In this way, auolese phones operated along the same premise as a hearing trumpet – amplifying close range sounds and helping to minimise background noise through more targeted and directional sound capture. However, unlike the hearing trumpet, the aurolese phone was designed to blend in with hairstyles or hats, negating complaints about the overly ostentatious nature of most contemporary hearing aids. The ‘invisibility’ of one’s hearing aid appears to have been an especially important factor for upper and middle-class women. Although the aurolese phones are not mentioned by name, the William V. Willis Company briefly advertised their book of ‘25 instruments to assist the hearing’ in the Ladies Home Journal for April 1902, p. 33. As we can see from the 1922 Transactions of the American Otological Society, the William V. Willis Company was known for its production of ‘auricles’ and that auricles were, in turn, believed to be a suitable device for women who wished to conceal their use of hearing aids.

Electrical Hearing Aid

Electrical Hearing Aid

In 1898, Miller Reese Hutchinson (an American electrical engineer) constructed the first portable electrical hearing aid – which he named the Akouphone. This device was inspired by Alexander Graham Bell and his invention of the telephone. Much like the telephone, the akouphone used a carbon microphone which could modulate electrical current and amplify sound. Unfortunately, the akouphone was expensive, heavy, and bulky – it weighed approximately three and a half pounds and was encased in a heavy rubber box! As such, it’s popularity was limited amongst individuals with hearing impairments, who continued to use cheaper, more portable devices such as the hearing trumpet. However, four years later, in 1902, Hutchinson improved upon the design of his akouphone. Whilst still using carbon microphones, he reduced the size and weight of the device and renamed it the ‘acousticon’. In the 1903 Association Review, Enoch Henry Currier praises Hutchinson’s improvements, claiming that ‘he has succeeded in perfecting a battery which is so small as to make it easy to be carried; the battery of course being the foundation upon which the effectiveness of the instruments rests’ (p. 200). Due to their ability to adapt, improve, and make use of new technologies, the Hutchinson Acoustic Company (which later became the General Acoustic Company) enjoyed great success and continued to produce hearing aids well into the 1980s.

Despite the early success of the carbon-based hearing aid, the 1920s saw the emergence of a new kind of electrical hearing aid which used vacuum tubes to amplify sound. Much like carbon hearing aids, early examples of vacuum hearing aids tended to be large and unwieldy. For example, the vactuphone (produced by the Globe Company in 1921) weighed around seven pounds! It was not until the later 1930s that two English companies – Amplivox of Wembley and Vernon-Spencer of London – produced wearable vacuum hearing aids. For Amplivox of Wembley, this was a ‘two-piece’ aid in which the batteries were separate from the hearing aid. For Vernon-Spencer of London, this was a more compact ‘one-piece’ aid, where the batteries were contained within the hearing aid case. An example of these wearable hearing aids can be seen at the end of a 1949 Encyclopaedia Britannica film titled The Ears and Hearing.

As has been a theme throughout this primary source set, these smaller electrical aids were praised for their subtlety. For example, in the January 1911 edition of The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review, the General Acoustic Co. advertise their hearing aids whilst claiming that, ‘ladies who use the Acousticon dress their hair so as to make the head-band and ear-piece invisible’. (p. 67). Similarly, in 1933, Margaret Prescott Montague wrote of her experience using an electrical hearing aid, stating that: ‘Upstairs in my own room I tried the thing out first. If it was not going to be a success – and probably it wasn’t – I preferred to be alone with my disappointment. I put it on. I heard the clock tick – farther, and father, and father away, I heard it – all across the room! And that when with my unaided ears I can barely hear it at the distance of an inch! Oh, joy! Still wearing the device, I ventured downstairs into the family circle, and said to my two kinsmen, ‘Look at me – do you notice anything?’ They looked me all over from head to foot, and then, doing their masculine best, offered hopefully, ‘Why you have on a new dress.’ And this a garment I had worn all winter. Joy again! The little thing was so inconspicuous that no one’s conversation was to be dried at the roots by the terrifying sight of an ear trumpet.’ (pp. 49-50).

Bibliography

Please find a list of the sources referenced in this set below.

- Acousticon Institute, ‘Acousticon’, Rhode Island Medical Journal, 24 (1941), VI

- American Dentaphone Co., The Dentaphone (Cincinnati: The American Dentaphone Co., 1879)

- Audiphone Parlours, The Audiphone (London: Waterlow and Sons Limited, 1882)

- Bacon, Francis, The Works of Francis Bacon, Vol. I (London: H. Bryer, 1803)

- Cozzolino, Vincenzo, The Hygiene of the Ear (London: Baillière, Tindall and Cox, 1892)

- Currier, Enoch Henry, ‘The Acousticon’, The Association Review, 5 (1903), 200

- Curtis, John Harrison, A Treatise on the Physiology and Diseases of the Ear (London: Printed for John Anderson, 1819)

- Curtis, John Harrison, A Treatise on the Physiology and Diseases of the Ear (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman, 1836)

- Down Bros Ltd., A Catalogue of Surgical Instruments and Appliances (London: Down Bros Ltd., 1906)

- General Acoustic Co., ‘Well, Well! I Hear You Perfectly Now!’, The Trained Nurse and Hospital Review, 46:1 (1911), 66

- Giles of Rome, Expositio Egidij[us] Romani Super Libros De Anima Cum Textu (Venice: Bonetus Locatellus for Octavianus Scotus, 1497)

- Hancock, Louis M., ‘Acousticon’, Nebraska State Medical Journal, 32:3 (1947), XXXV

- Montague, Margaret Prescott, The Lucky Lady (Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1933)

- Phillips, Wendell C., ‘The Otologist in the Field of Sociology’, Transactions of the American Otological Society, 16:1 (1922), 432-461

- Porta, John Baptista, Natural Magick (London: Printed for John Wright, 1669)

- Rhodes & McClure, The Audiphone (Chicago: Rhodes & McClure, 1880)

- Staffe, Baronne, My Lady’s Dressing Room (New York: Cassell Publishing Company, 1892)

- The Ears and Hearing, prod. by Encyclopedia Britannica Films Inc. (Encyclopedia Britannica Films Inc., 1949)

- Turnbull, Laurence, Imperfect Hearing and the Hygiene of the Ear (Philadelphia : Lippincott, 1881)

- Willis, William V., & Co., ‘Deaf?’, The Ladies’ Home Journal, Easter (1902), 33